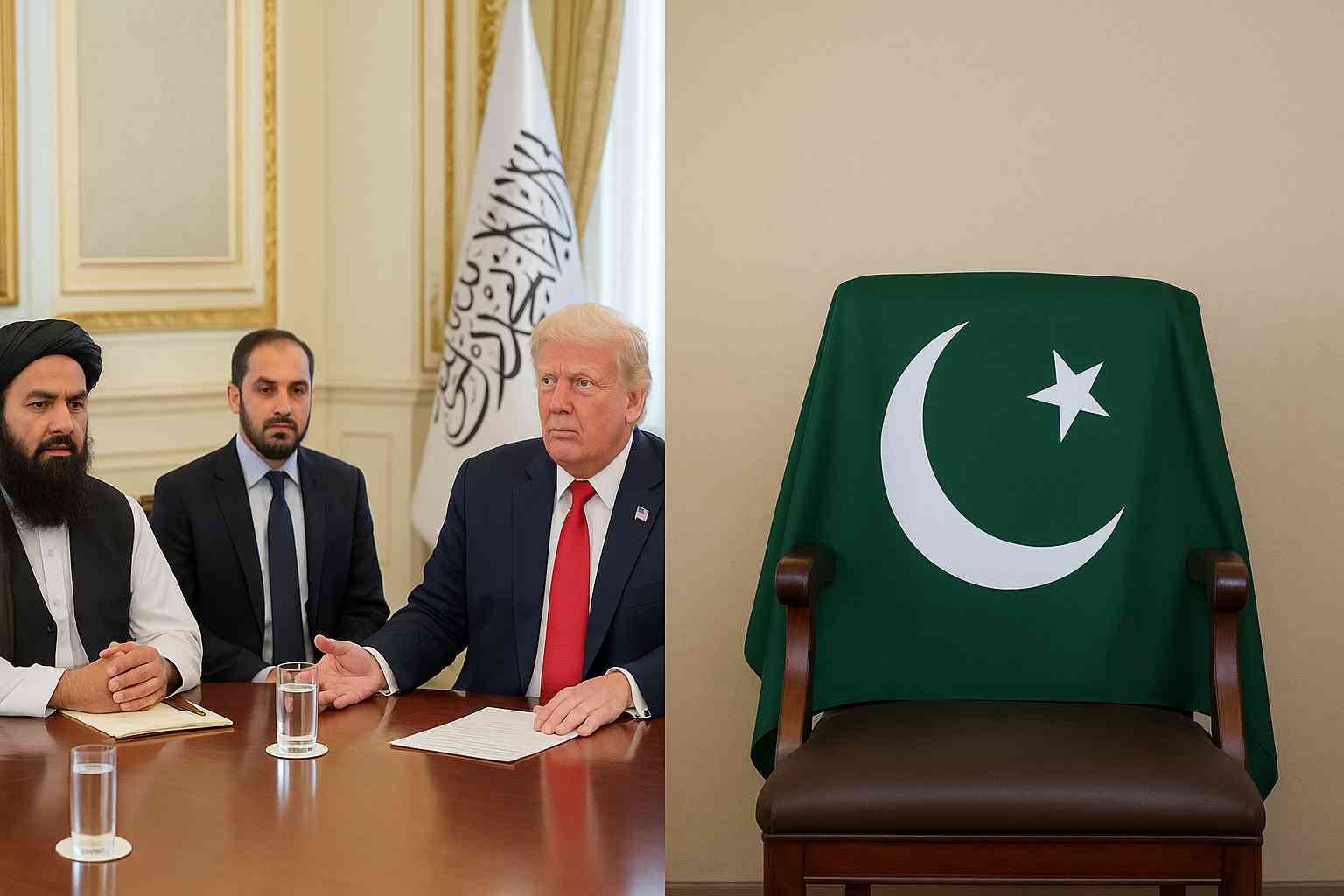

At first glance, the story seems almost unbelievable. A nuclear-armed state approached a Western democracy with an informal proposal to swap convicted sex offenders for political dissidents. However, this episode represents a stark case of cross-border repression, according to a detailed investigation published by DropSite News. The report reveals that the proposal emerged during a quiet, closed-door meeting in Islamabad between Pakistan’s Interior Minister Mohsin Naqvi and the UK’s High Commissioner, Jane Marriott.

At the centre of the discussion stood a startling bargain. Pakistan, after years of refusing to accept convicted members of the Rochdale grooming gang, suddenly signalled its willingness to take them back. In return, it demanded the extradition of two outspoken critics living in the UK: former federal minister and barrister Shehzad Akbar, and myself, a journalist and retired army officer.

The message was unmistakable. The Pakistani government now treats dissidents as commodities in a geopolitical transaction. It places them on the same moral and legal plane as convicted child abusers. This is not diplomacy. Instead, this is cross-border repression at its most brazen.

The UK’s Dilemma: A Political Headache Meets an Authoritarian Opportunity

For years, the British government has struggled with the political fallout from the Rochdale grooming gang. In 2018, authorities stripped several perpetrators, including Qari Abdul Rauf and Adil Khan, of their citizenship. However, deportation efforts stalled because Pakistan refused to recognise them as nationals after they voluntarily renounced citizenship.

As a result, this legal limbo fuelled sustained public anger in the UK. Right-wing activists such as Tommy Robinson capitalised on the issue. They accused successive governments of weakness and hypocrisy. Meanwhile, tech billionaire Elon Musk amplified these narratives globally by repeatedly tweeting in support of Robinson’s anti-government campaigns.

For the current UK administration, finally deporting these offenders would therefore represent a significant domestic victory. Pakistan’s military-backed government understands this pressure well. Consequently, it is exploiting the moment to silence critics abroad through cross-border repression.

Why Pakistan Wants Dissidents — And Why Now

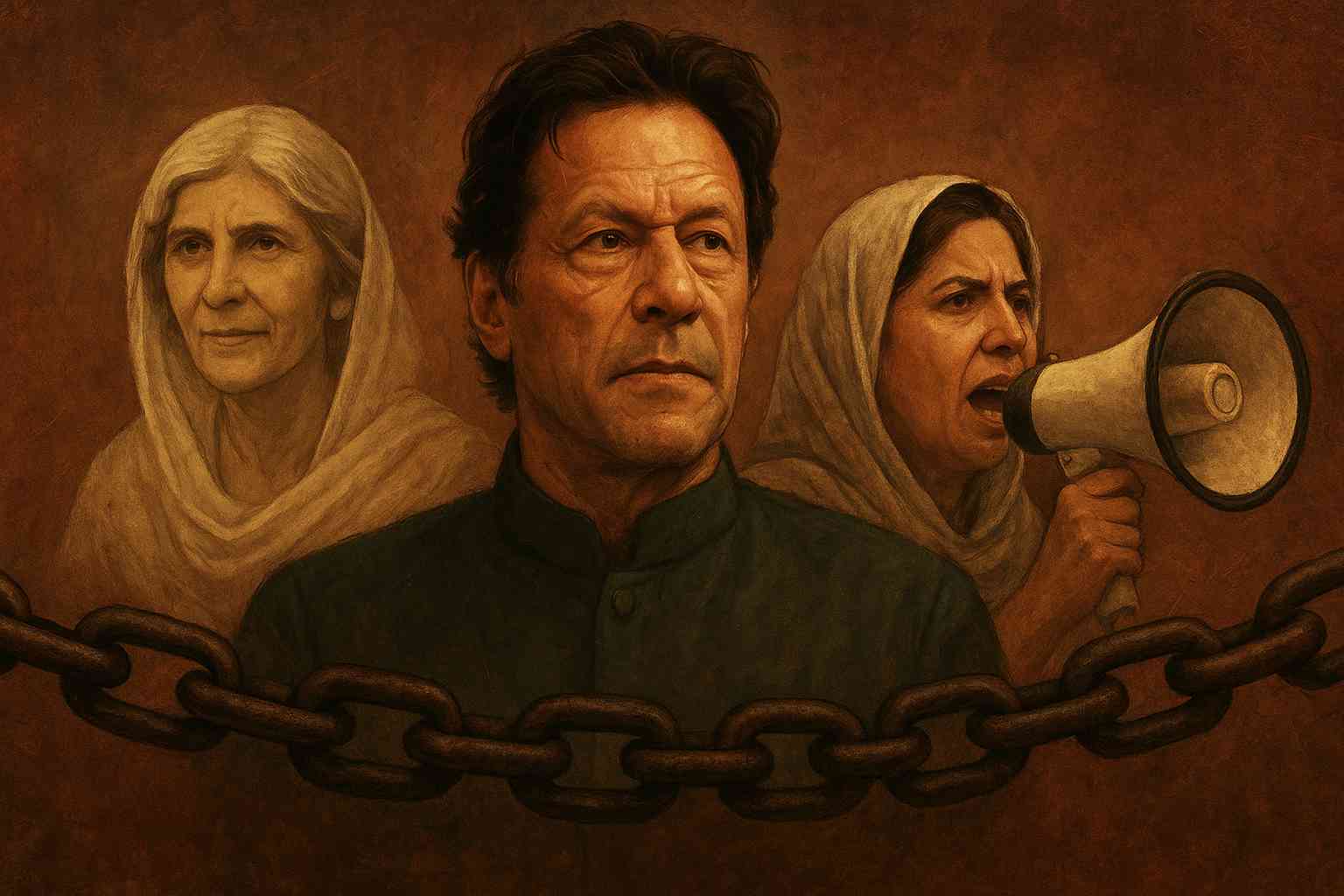

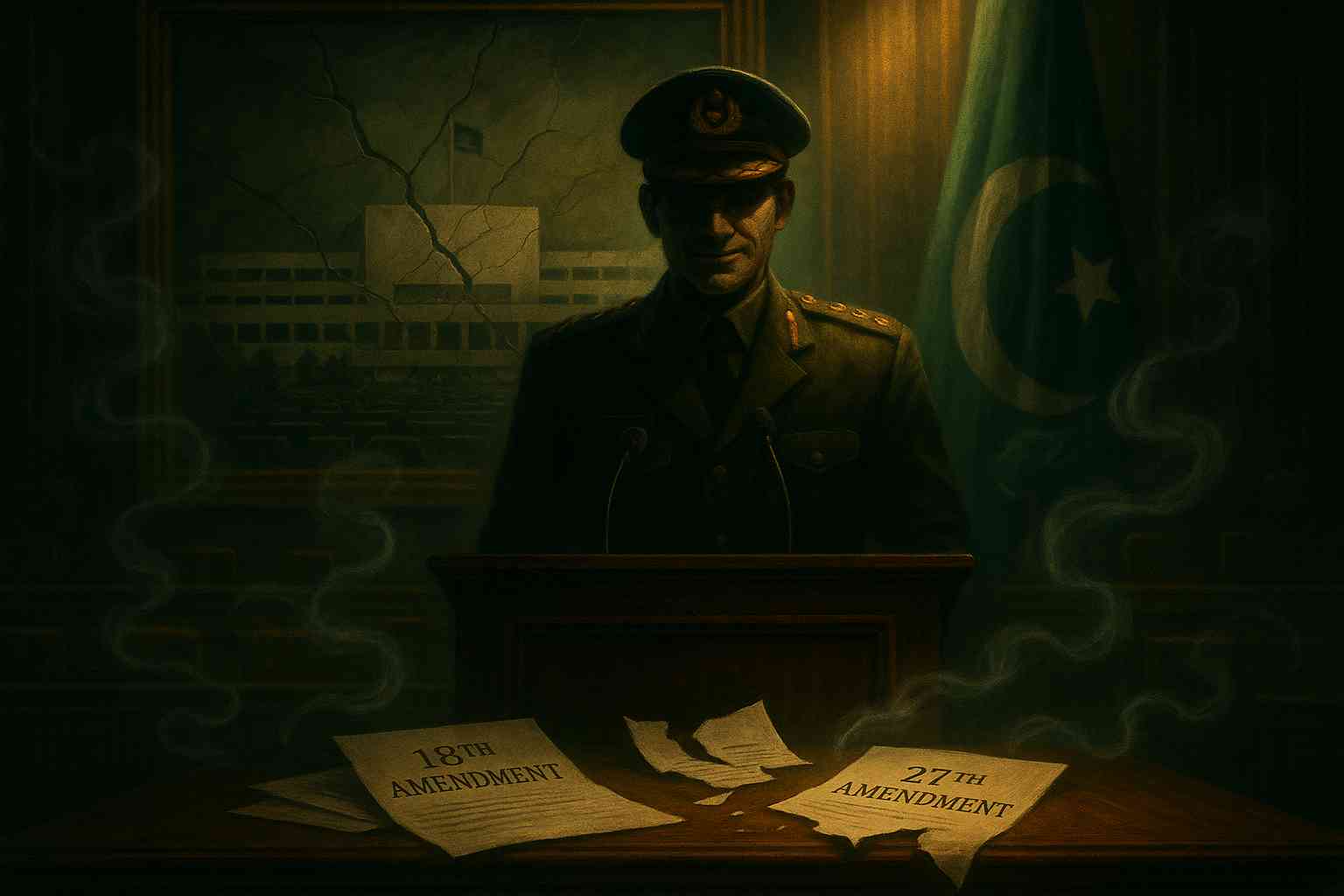

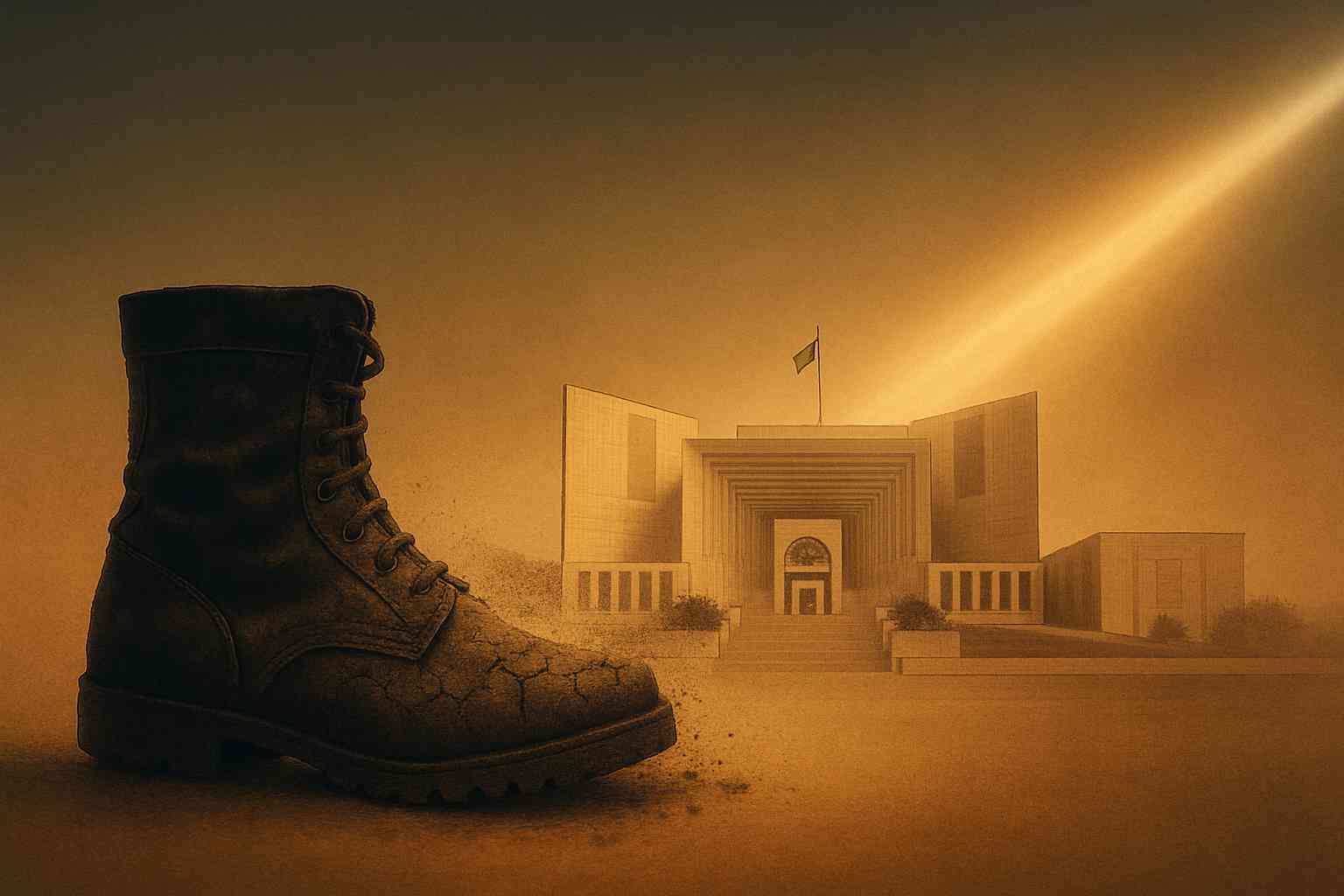

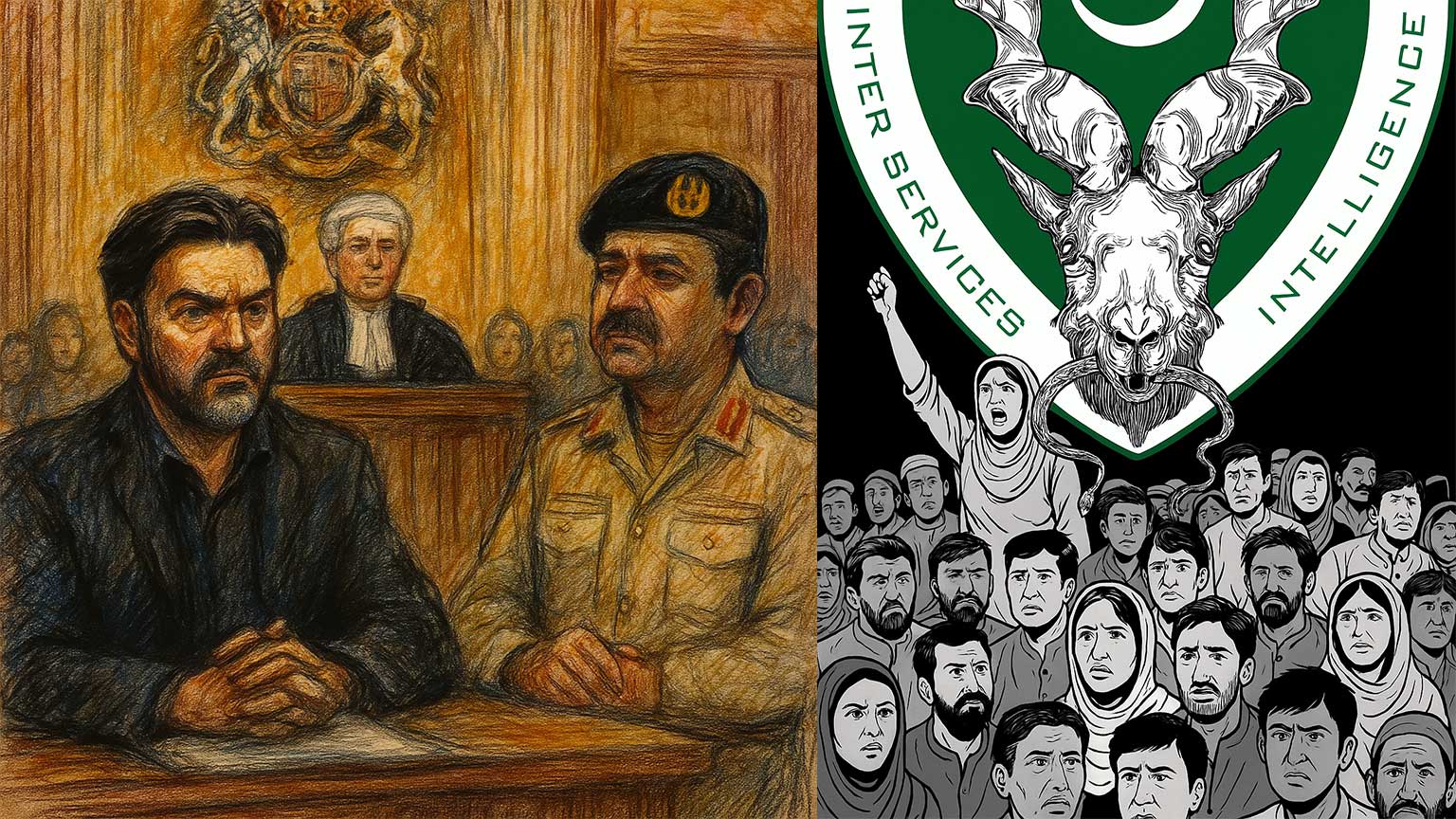

In recent years, Pakistan has suffered an unprecedented collapse of democratic norms. Security agencies have abducted journalists. Authorities have imprisoned political opponents. Military courts have tried civilians. Meanwhile, constitutional amendments have entrenched the power of Field Marshal Asim Munir, now elevated to Chief of Defence Forces with lifetime immunity.

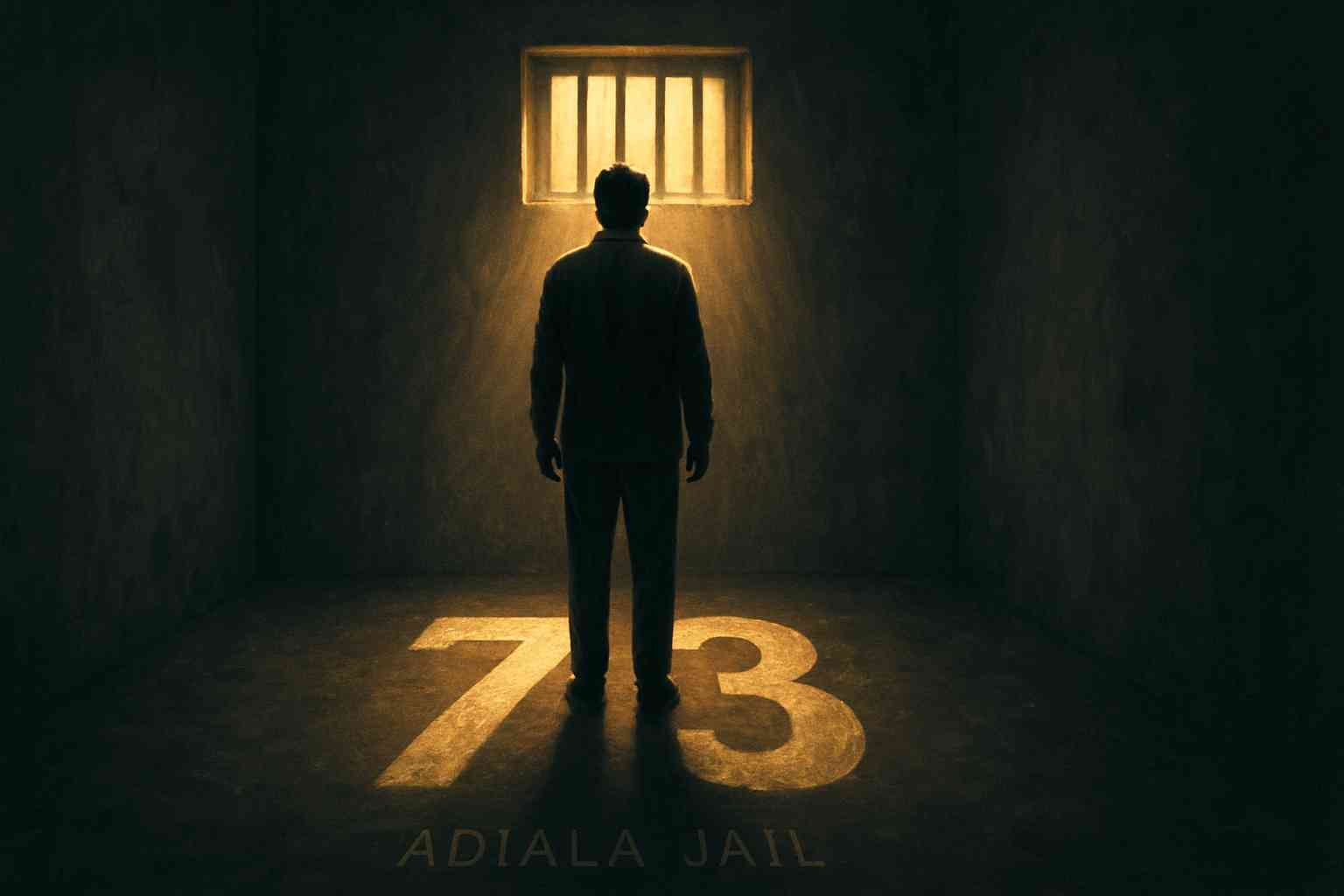

At the same time, the incarceration of former Prime Minister Imran Khan has paralysed the political system. As dissent inside Pakistan has become increasingly dangerous, the final space for free political expression has shifted abroad. In particular, members of the Pakistani diaspora with uncensored platforms now play a critical role.

This group includes journalists like myself and human-rights advocates such as Shehzad Akbar. Our work exposes corruption, constitutional violations, enforced disappearances, and extrajudicial abuses. As a result, we now stand in direct confrontation with the state.

To silence these voices, Pakistan has moved beyond domestic repression. Instead, it has escalated into cross-border repression, deploying legal, diplomatic, and coercive tools far beyond its territory.

A Pattern of Persecution: From Passport Cancellation to SLAPP Lawsuits

To understand the gravity of this latest extradition attempt, one must view it in context. Over the past few years, the Pakistani state has taken an escalating series of actions against me:

- Cancellation of my national ID and passport, rendering me effectively stateless.

- Seizure of my assets and bank accounts in Pakistan.

- A court-martial in absentia, sentencing me to 14 years without legal representation or due process.

- The abduction of my mother, who remains under surveillance and barred from leaving Pakistan.

- A counterterrorism case brought against me in the UK, which concluded with No Further Action.

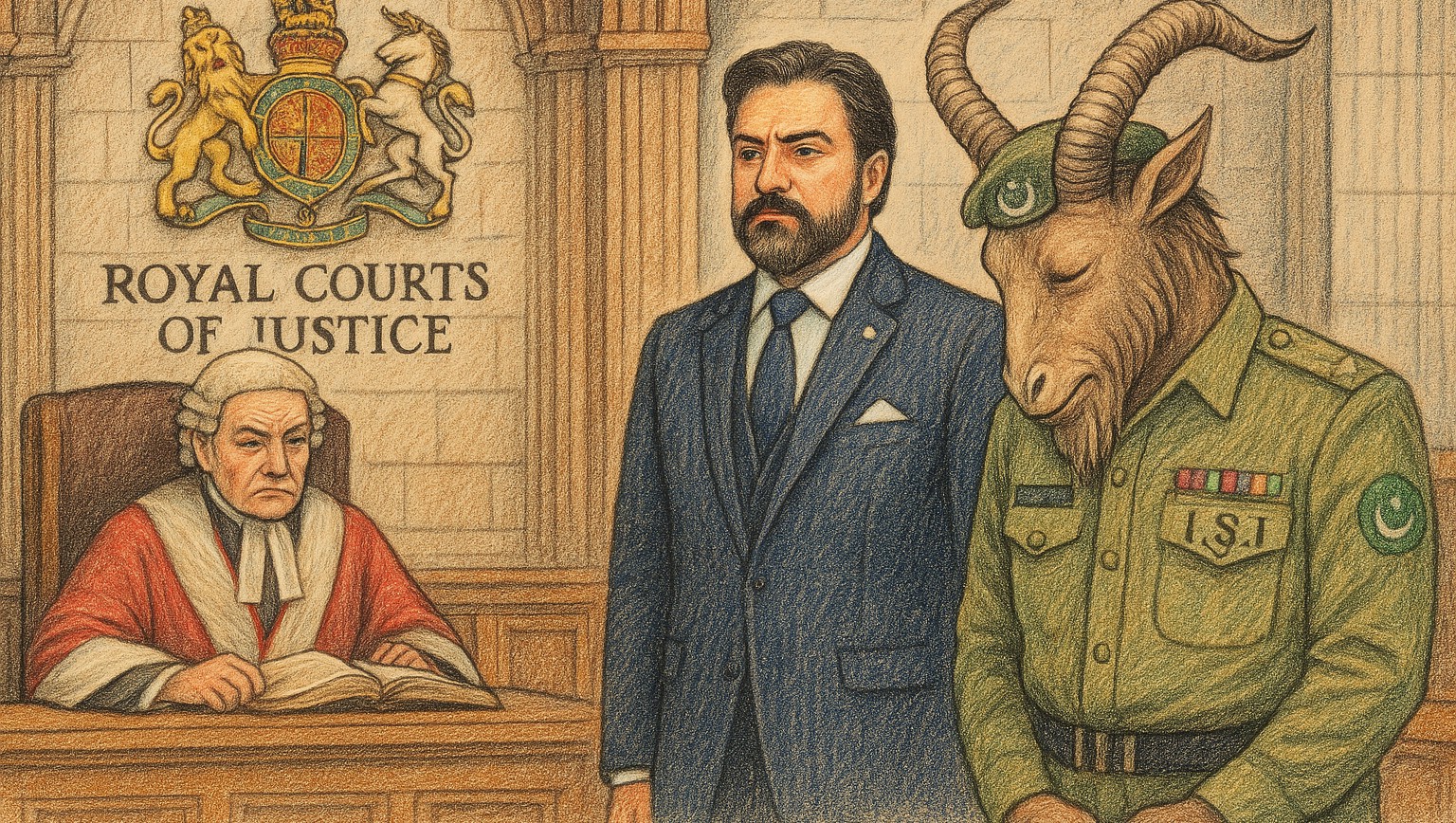

- A Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation (SLAPP) in the High Court of London, designed to intimidate, discredit, and financially exhaust me.

Taken together, these actions reflect textbook tactics of transnational authoritarianism. They rely on coercion, intimidation, legal abuse, and family targeting. Moreover, UN Special Rapporteurs on Torture, Human Rights Defenders, and Freedom of Expression have repeatedly condemned such methods. The grooming-gang swap proposal simply marks the next step. Most shockingly, it openly confirms Pakistan’s readiness to weaponise diplomacy as a tool of cross-border repression.

The Legal Barrier: UK Protections Against Politically Motivated Extradition

Despite the sensational nature of the proposed exchange, legal experts note that the UK cannot extradite political dissidents to regimes where they face persecution, torture, or unfair trial.

Under British law and international treaties:

- Political motivation invalidates extradition requests.

- Individuals cannot be returned to states where they face torture or cruel treatment (Article 3, Convention Against Torture).

- Extradition is barred if the requesting state lacks independent courts and due process (UK Extradition Act).

- Freedom of expression is explicitly protected under the European Convention on Human Rights, including criticism of foreign governments.

Pakistan fails every one of these tests.

International monitors consistently rank the country among the world’s most dangerous for journalists. Over the past decade, dozens have been killed, hundreds abducted, and thousands forced into exile. Torture in custody remains well documented. Political trials routinely lack transparency. Therefore, any extradition under such conditions would be both unlawful and immoral.

A Grim Precedent for the Global Crackdown on Dissent

Beyond the personal stakes for those involved, this episode represents a disturbing precedent. If authoritarian states begin offering Western governments “political wins” in exchange for dissidents, the global environment for journalists, whistle-blowers, and human-rights defenders becomes exponentially more dangerous.

It would signal that:

- Exiled critics can be traded like diplomatic tokens.

- Repressive regimes can exploit Western domestic politics to advance their agendas.

- Safety abroad is conditional, precarious, and negotiable.

Such a precedent threatens the very concept of political asylum and undermines the international system built to prevent persecution across borders.

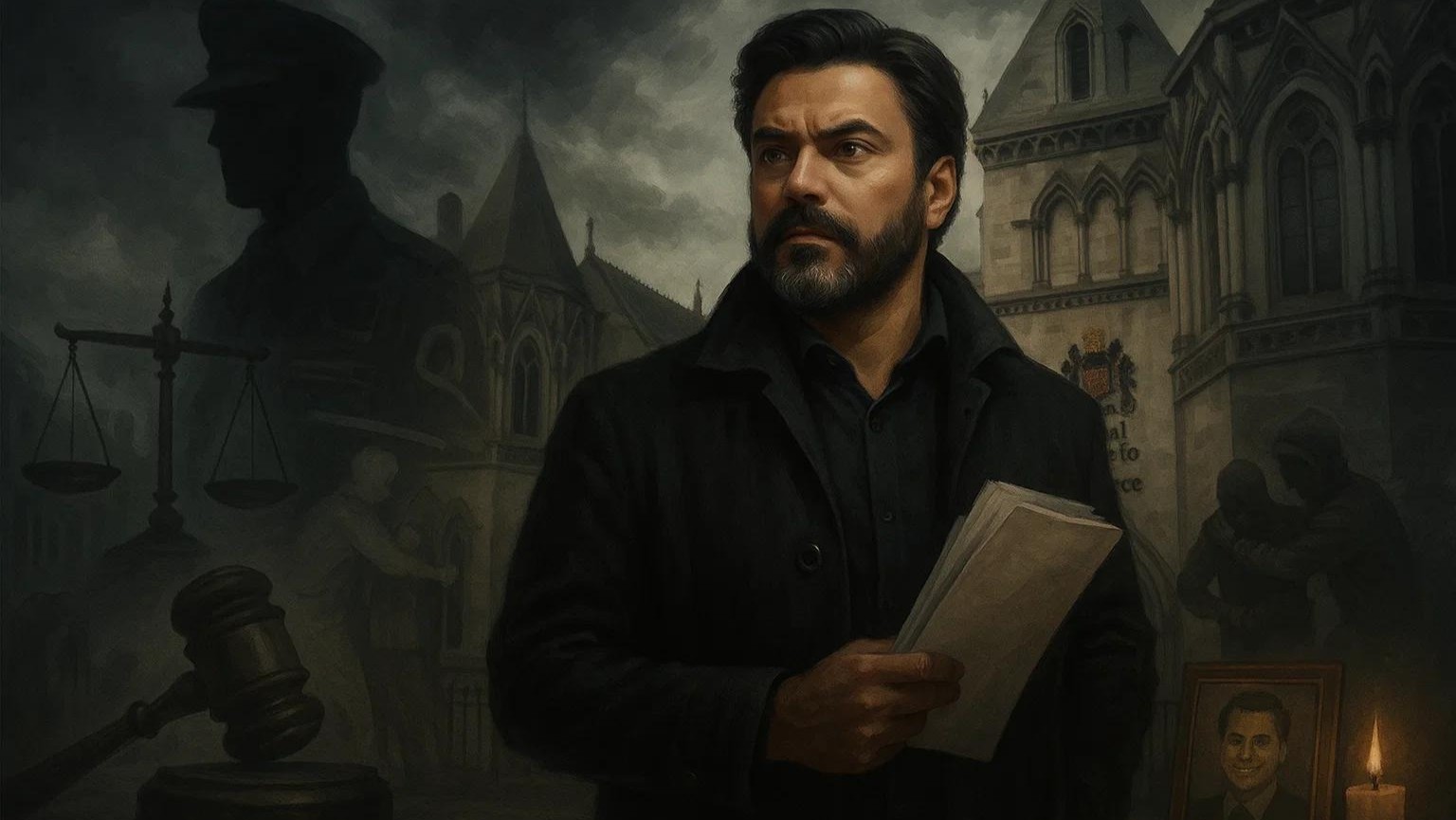

My Response—and a Call for International Attention

In response to the report, I have made it clear that I have committed no crime under UK law. My only “offence” is the practice of free journalism, exposing state overreach and human-rights violations.

If criticising a government is “anti-state propaganda,” then every journalist becomes a criminal. If speaking truth is punishable, then the state ceases to be democratic.

The international community must recognise that my case is not isolated. It is part of a broad strategy by Pakistan’s military establishment to suppress dissent everywhere—even beyond its borders.

With Pakistan now resorting to bartering criminals for critics, the urgency for international scrutiny cannot be overstated.

A Test for Both Governments

For Pakistan, this episode reveals the extent of institutional decay and democratic erosion under military dominance. For the UK, it is a test of principle: will the government uphold its commitments to human rights and free expression, or succumb to political pressure? The choice will define the safety of dissidents and journalists on British soil for years to come.

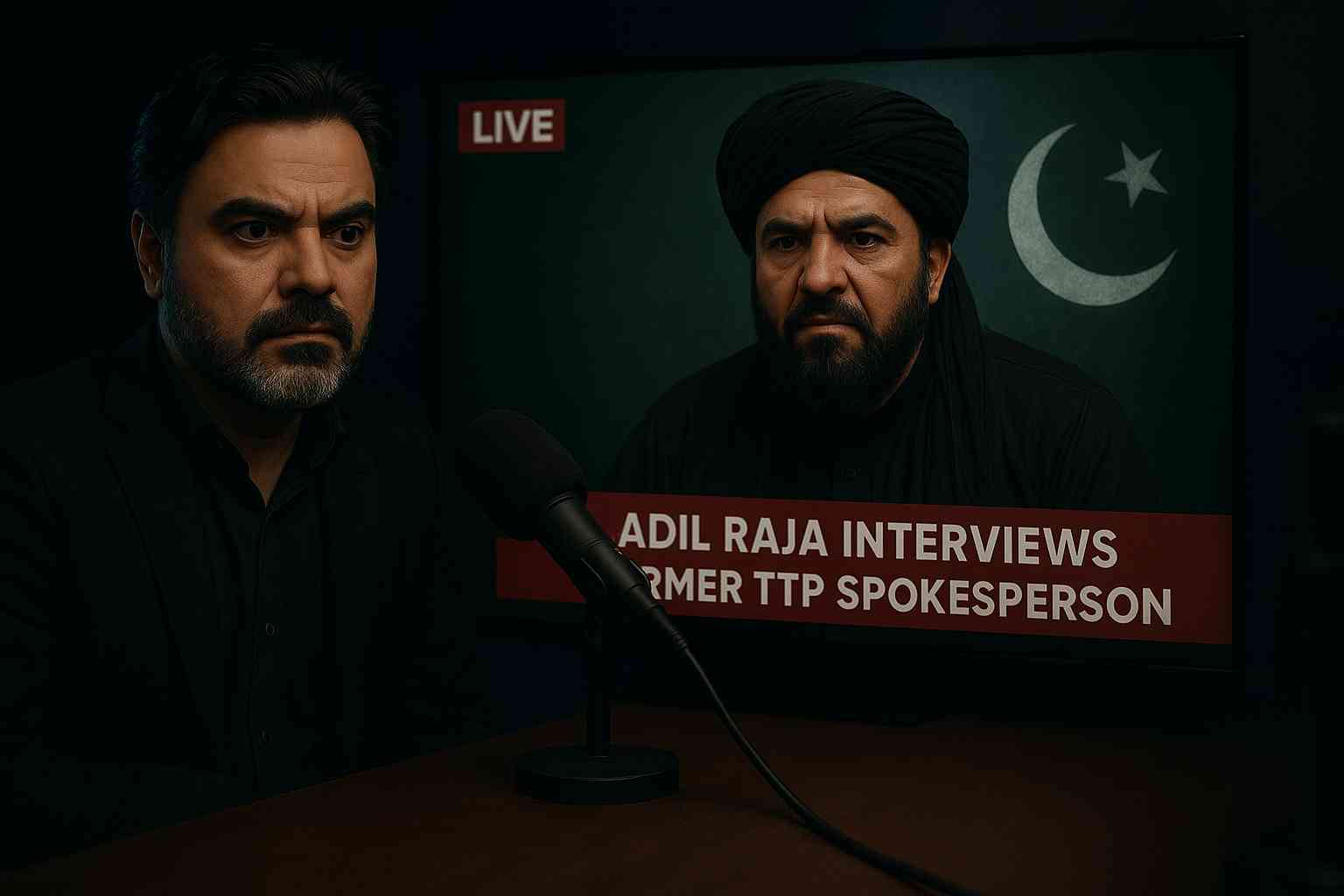

Adil Raja is a retired major of the Pakistan Army, freelance investigative journalist, and dissident based in London, United Kingdom. He is the host of “Soldier Speaks Reloaded,” an independent commentary platform focused on South Asian politics and security affairs. Adil is also a member of the National Union of Journalists (UK) and the International Human Rights Foundation. Read more about Adil Raja.. Read more about Adil Raja.