“Soon the nations will call one another to attack you as diners call one another to a dish.” Someone asked, “Will it be because we are few in numbers on that day?” He said, “No, rather you will be many on that day, but you will be like the scum, the dirt and refuse on the surface of flood water. Allah will take away your fear from the hearts of your enemies, and Allah will fill your hearts with Wahn (weakness).” One of the companions asked: “What is this ‘Wahn’, O Messenger of Allah?” He replied, “Love of this world and dislike for death.” (Sunan Abi Dawud 4297)

Sudan perhaps is one of those Muslim countries where manifestation of this hadith becomes explicit.

Brief Synopsis:

Two years ago in April, conflict broke out between the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), displacing millions of people, driving the country into severe food insecurity, and devastating essential health and education systems. Despite the scale of this humanitarian catastrophe, Sudan’s war has largely remained outside the global spotlight. What geopolitical dynamics make Sudan such a contested and desirable battleground?

Introduction:

The name Sudan originates from the Arabic phrase bilād al-sūdān, meaning “land of the blacks”, a term medieval Arab geographers used to describe the settled African regions lying just south of the Sahara. Since antiquity, the Sudan region has served as a crossroads between the cultural traditions of Africa and those of the Mediterranean world. Over time, Islam and the Arabic language became dominant in the northern areas, while older African languages and cultures remained prevalent in the south.

These longstanding cultural and linguistic divisions, intensified by decades of civil war between the north and the south, ultimately culminated in the 2011 referendum that formalized the split of the country into two independent states: Sudan and South Sudan.

Geostrategic Posture:

Sudan was once Africa’s third-largest country and the sixteenth-largest worldwide. It shares borders with Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the northeast, Eritrea to the east, Ethiopia to the southeast, the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Libya to the northwest, and South Sudan to the south. The territory of Sudan, together with what is now South Sudan, is also traversed by the Nile River, the longest river in the world.

Mineral wealth:

Sudan has a long history and a big heritage of Mining culture which goes back to three thousand years when Nubians (ancient Nilo-Saharan Indigenous groups) extracted gold and base metals and smelted iron to make water wells.

Sudan possesses an exceptionally rich array of mineral resources, including gold, petroleum, natural gas, uranium, chromite, and iron ore, along with asbestos, cobalt, copper, granite, gypsum, kaolin, tin, manganese, mica, nickel, silver, and zinc. The country is also endowed with highly fertile agricultural land, sustained by the flow of the legendary Nile River. Although the available statistics are significantly distorted, we will refrain from delving into them and instead keep in mind that gold remains the central and most obscuring factor.

Geographically, Sudan occupies a pivotal position along two major natural features: the Nile River and the Red Sea. Together, these locations confer significant strategic value, enhancing the country’s importance in trade, resource access, and regional transportation.

Structural layers of the Conflict

Dubbed by The Economist as “The Engine of Chaos,” Sudan indeed functions as a regional flashpoint capable of sending shockwaves across Africa and the Middle East. Since neither the SAF nor the RSF can win alone, both sought money, arms and at times direct intervention, as opportunities ruthlessly exploited by outside powers with vested interests, layering the conflict with complex geopolitical stakes. We will break down these dynamics by exploring local and regional (Nile bound) and global dimensions separately.

- Local; Paramilitary Industrial Axis

Omar Al-Bashir, a brigadier general in the Sudanese Army, seized the presidency in 1989 after a coup that toppled the democratically elected Prime Minister Sadiq al-Mahdi. History seemed to repeat itself—twice—when the SAF launched its first military coup in 2019, ending Al-Bashir’s 30-year rule. A brief return to a hybrid military-civilian government proved short-lived. In October 2021, a second coup unfolded, this time led by two powerful figures: General Abdel Fatah al-Burhan of the SAF and General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, better known as “Hemedeti,” of the RSF. Sudan was once again plunged into political upheaval.

Ironically, RSF was organized by Al-Bashir in 2013 as force against African insurgents in Darfur. Their leader, General Mohamed Hamdan “Hemedti” Dagalo, and his fighters have evolved significantly from their beginnings as a ragtag Arab militia, once widely disparaged as the “Janjaweed”. In addition to this, RSF relies on Hemedti family business centered around gold mines. This ecosystem of money, weapons, and gold defines the Paramilitary-Industrial complex.

In contrast, the SAF has been deeply entrenched in Sudan’s political, social, and economic spheres since the 1950s. This long-standing influence gave the SAF a foothold in the system, allowing it to create a repressive environment that limited the RSF’s operations across commercial, industrial, and agricultural sectors. We can have glimpse of military-industrial rot from the fact that in May 2020, Sudanese Ministry of Defense alone had more than 200 companies with annual revenue of 110 billion Sudanese pounds ($2 billion according to official exchange rate of that time). RSF, on the other hand, had 250 companies, in addition to significant revenue from mercenary businesses. According to a comprehensive review by researcher and political analyst Jean-Baptiste Gallopin, these military companies are involved in the production and sale of gold and other minerals, marble, leather, livestock, and gum Arabic. They are also involved in import trade—including controlling 60 percent of the market related to the lives of many people.

- Regional Conflict of Interest

River Nile is the second longest river in the world that passes through 11 African countries; Egypt, Sudan, South Sudan, Ethiopia, Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Eritrea, which makes the riparian states. It is vital for the sustainability of meeting the water needs of the countries it passes from. Sudan is one of those countries that occupy a major portion of this river.

In 1929, British agreed to give substantial control of river Nile to Egypt, including the power to veto construction projects on the river or any of its tributaries. This granted Egypt with a whooping 48 billion cubic meters of water and 4 billion cubic meters to Sudan, out of estimated average yield of 85 billion cubic meters.

The 1959 Egypt–Sudan agreement reaffirmed the 1929 Anglo-Egyptian Treaty and raised Egypt’s Nile allocation from 48 to 55.5 billion cubic meters and Sudan’s from 4 to 18.5 billion cubic meters, with 10 billion cubic meters set aside for seepage and evaporation. It also required that any increase in average flow be shared equally.

Like the 1929 treaty, it unjustly ignored the needs of other riparian states, including Ethiopia, which supplies over 80 percent of the Nile’s waters. This unfair divide deepened the grievances of neighboring countries as their increasing population pushed them towards developing more water holding capacity. Soon after gaining independence from Britain in 1961, Tanzania’s leader Julius Nyerere argued that the Nile Waters Agreements placed his country and other upstream states at Egypt’s mercy. He contended that the treaties effectively required them to subject their development plans to Cairo’s oversight, a position incompatible with sovereign statehood. Since then, all upstream riparian states have advocated for a new, more inclusive legal framework to govern the Nile Basin.

- Global Actors and the Red Sea:

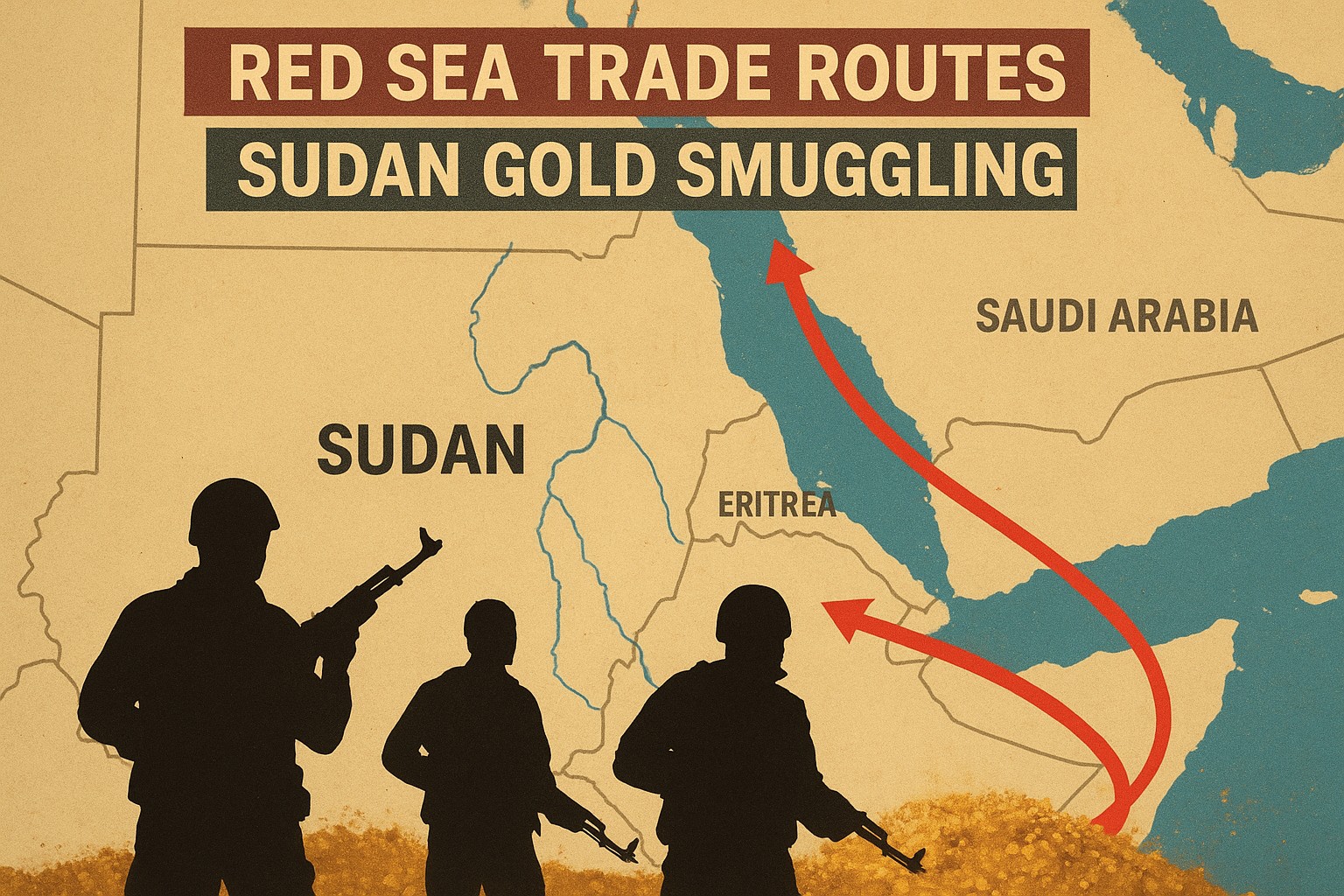

Whenever the Red Sea is mentioned, the Suez Canal immediately comes to mind. This route is a vital artery for global trade, with an estimated 12–15 percent of the world’s maritime commerce, worth over $1 trillion annually, flowing through it. Its strategic significance is magnified by the interests of key regional players, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt and Russia, adding further complexity to the crisis in Sudan. Geographically, Sudan lies just 30 km across the Red Sea from Saudi Arabia, making it highly accessible to foreign commercial and strategic interests.

Sudan’s coastline stretches 800km long along the red sea. With a costal border as long and volatile as that, internal strife open doors for foreign elements to enter and the discord to extend to neighboring regions particularly around the horn of Africa and East Africa, a region infested with foreign bases.

Sudan’s gold industry has become the lifeblood of its war, enriching both the army and paramilitaries. However, there is a method to this madness when considering alien actors. UAE aims to expand its influences in Sudan and gain further access to its gold laden mines. An estimated 50-80% (around 60 tonnes) of Sudanese gold is smuggled primarily to and through the UAE, with its true value two to three times higher than the official figures. Furthermore, the UAE has trained soldiers from neighboring African countries including Chad, Egypt and Eritrea; countries that are a part of moving contrabands form Sudan.

Egypt’s support for SAF primarily reflects the tendencies shown by ex-army chief President Abul Fattah Al-Sisi himself after he toppled Muhammad Morsi’s government back in 2013; talk about birds of feathers perhaps. Nonetheless, Egypt’s support for SAF is not unrestrained due to its heavy reliance on UAE’s support that enables Sisi to continue.

Saudi Arabia, a supporter of the SAF, considers the Red Sea as a pivot to Vision 2030 and its strategy for reducing reliance on oil and broadening the national economy. A major pillar of this plan is building tourism infrastructure along the Red Sea to draw global visitors. Continued conflict and extremist activity in the area risks undermining these goals, including the $500 billion NEOM mega-project.

For Russia, preserving its influence in the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean is strategically important, as it could affect control over the Suez Canal. Moscow is effectively playing both sides of the conflict. In exchange for backing al-Burhan and Hemedti, the Wagner Group, a Russian paramilitary organization, secures access to gold worth billions of dollars.

Conclusion

These intertwined local, regional, and global dynamics demonstrate that—even if the conflict in Sudan were to end soon—it has already destabilized the region and intensified both internal and cross-border tensions. From an Islamic perspective, geopolitical strength is grounded not only in natural resources and strategic location but also in principled leadership and a societal order guided by revelation. The Sudanese experience highlights a crucial lesson: weak, self-interested, and oppressive leadership creates the conditions for national collapse, leaving the Sudanese people vulnerable to external exploitation and interference. The Hadith mentioned at the opening of this paper serves as a policy guideline for us in current times to first and foremost, disassociate ourselves from Wahn; the love for the world and dislike for death.

Ali Khan is an independent contractor in the trucking industry with a background in Electrical Engineering. Passionate about politics and current affairs, he closely follows global and regional developments to offer grounded, people-centric perspectives on contemporary issues.