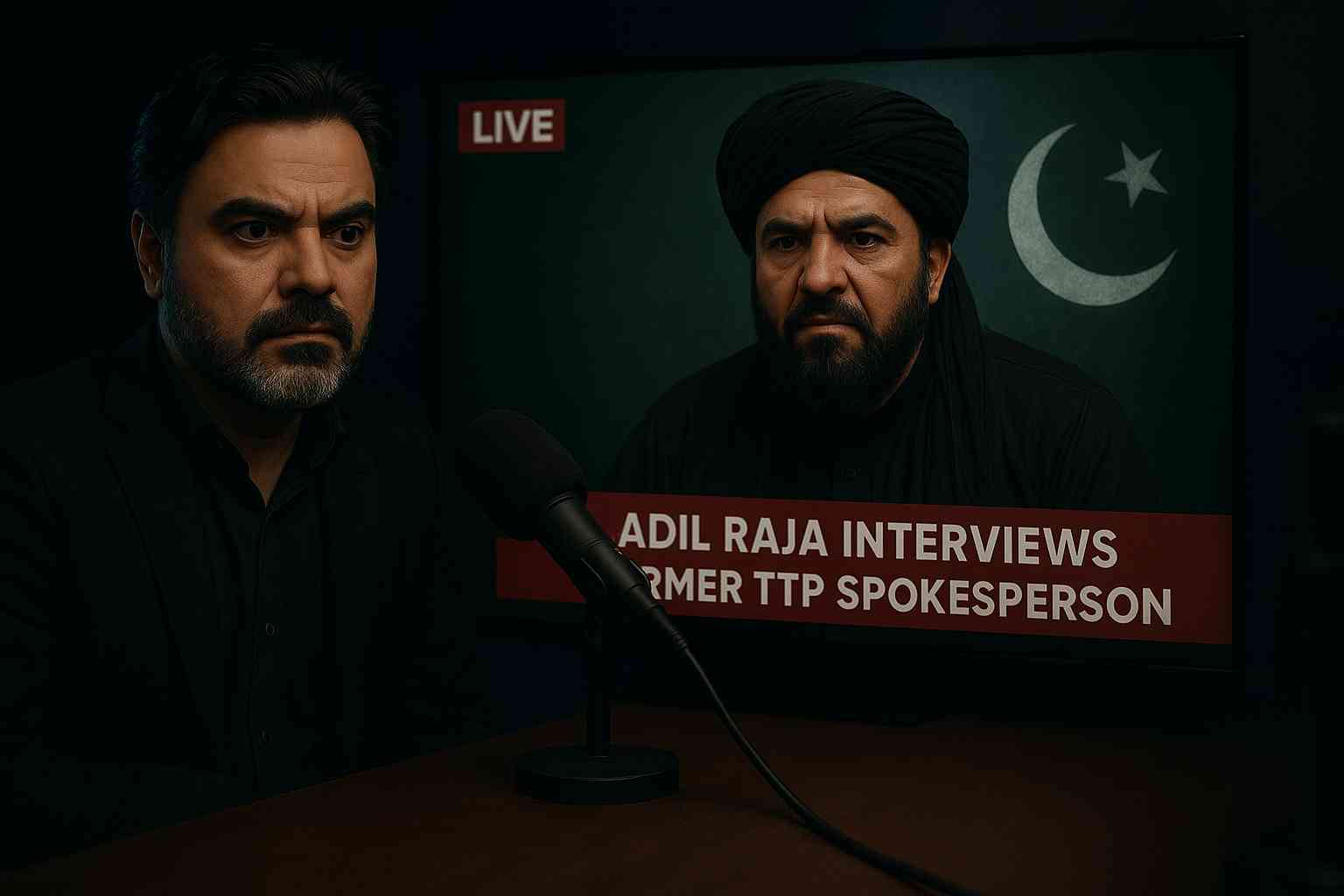

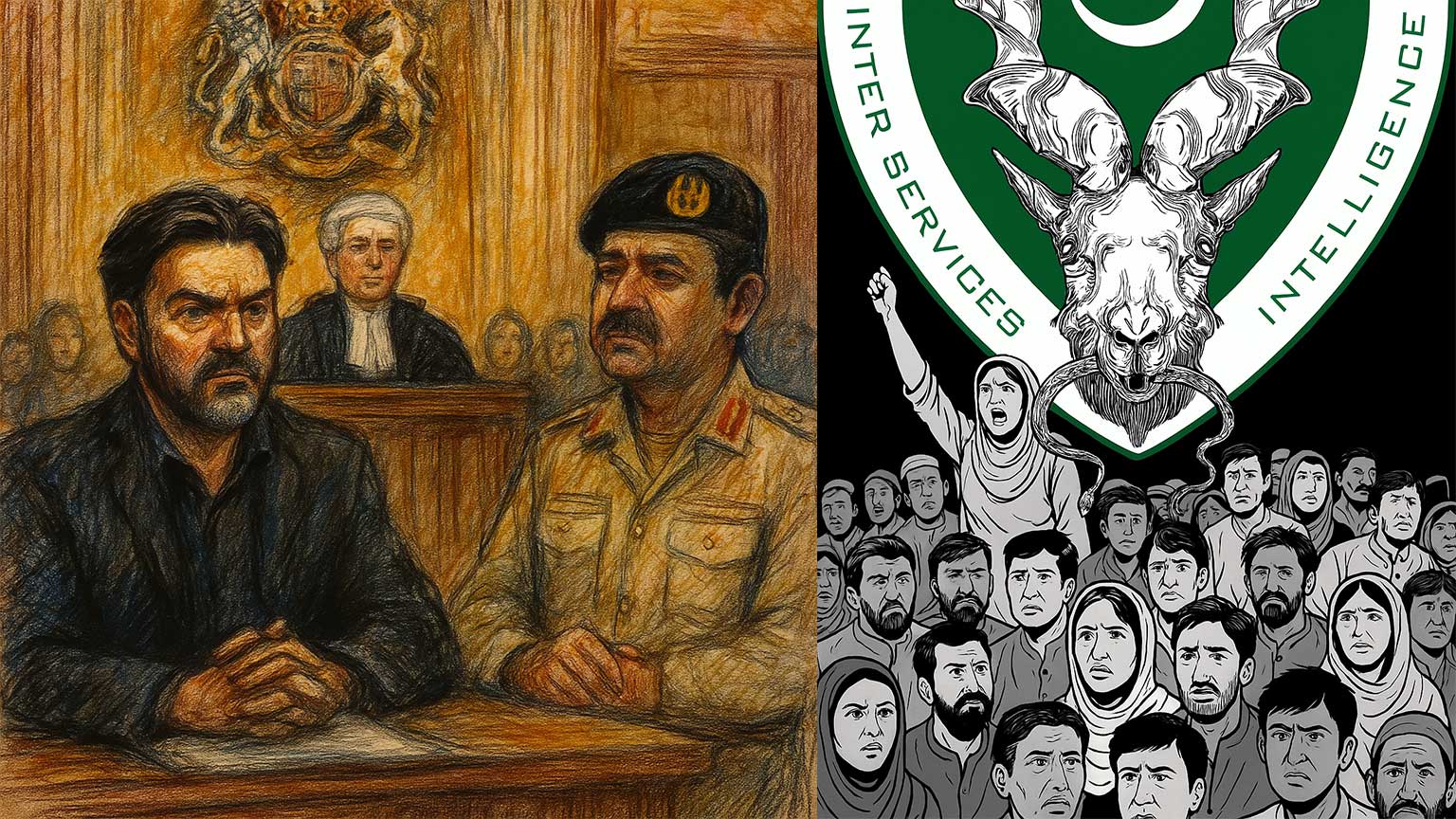

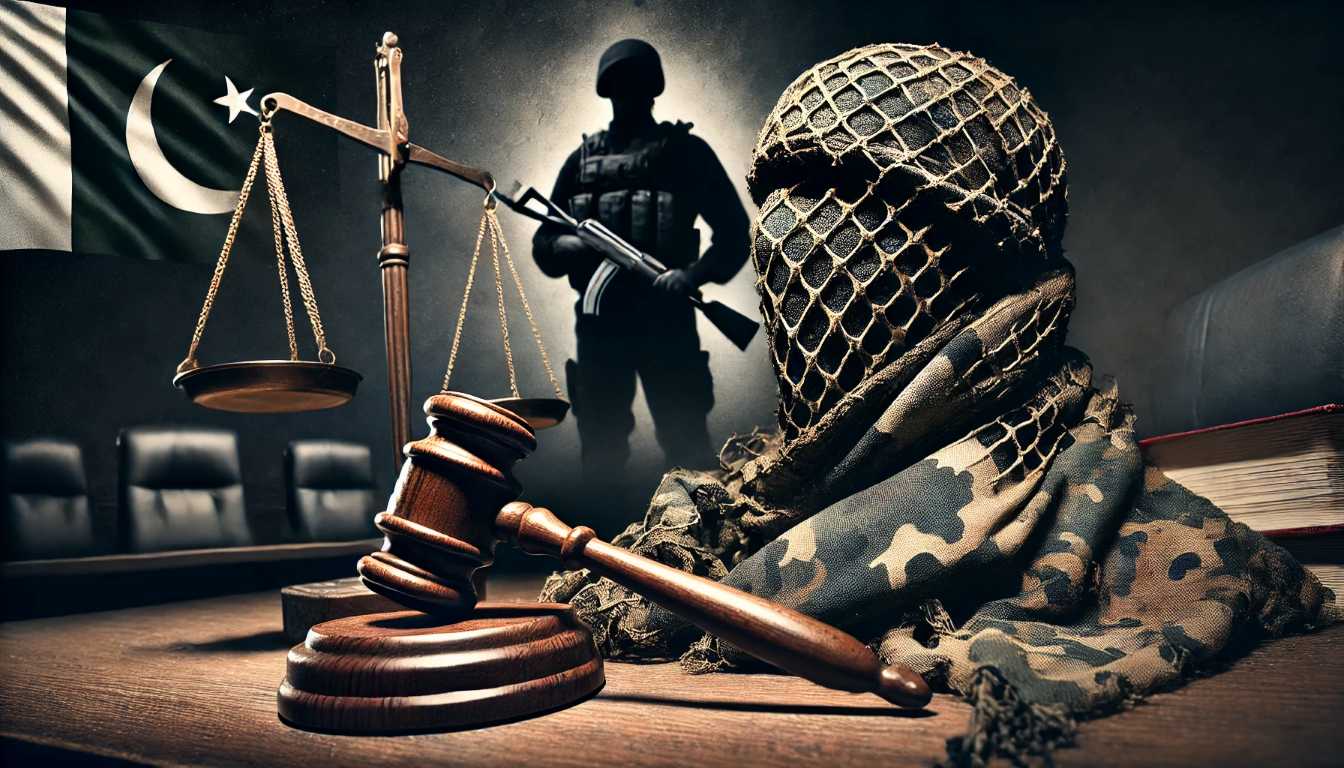

This high-profile defamation trial between former Pakistani ISI Brigadier Rashid Naseer and political commentator and investigative journalist Adil Raja centred around allegations of election rigging, ISI interference in Pakistan’s judiciary, and death threats. It evolved into a broader examination of journalism, state-sponsored intimidation, freedom of expression, and whistleblowing within Pakistan’s intelligence and military institutions.

The case revolved around the claim by Rashid Naseer, allegedly nicknamed “Lucy” by his course mates at PMA due to his effeminate behaviour. That persona became an unspoken thread throughout, echoing deeper questions of identity, influence, and insecurity.

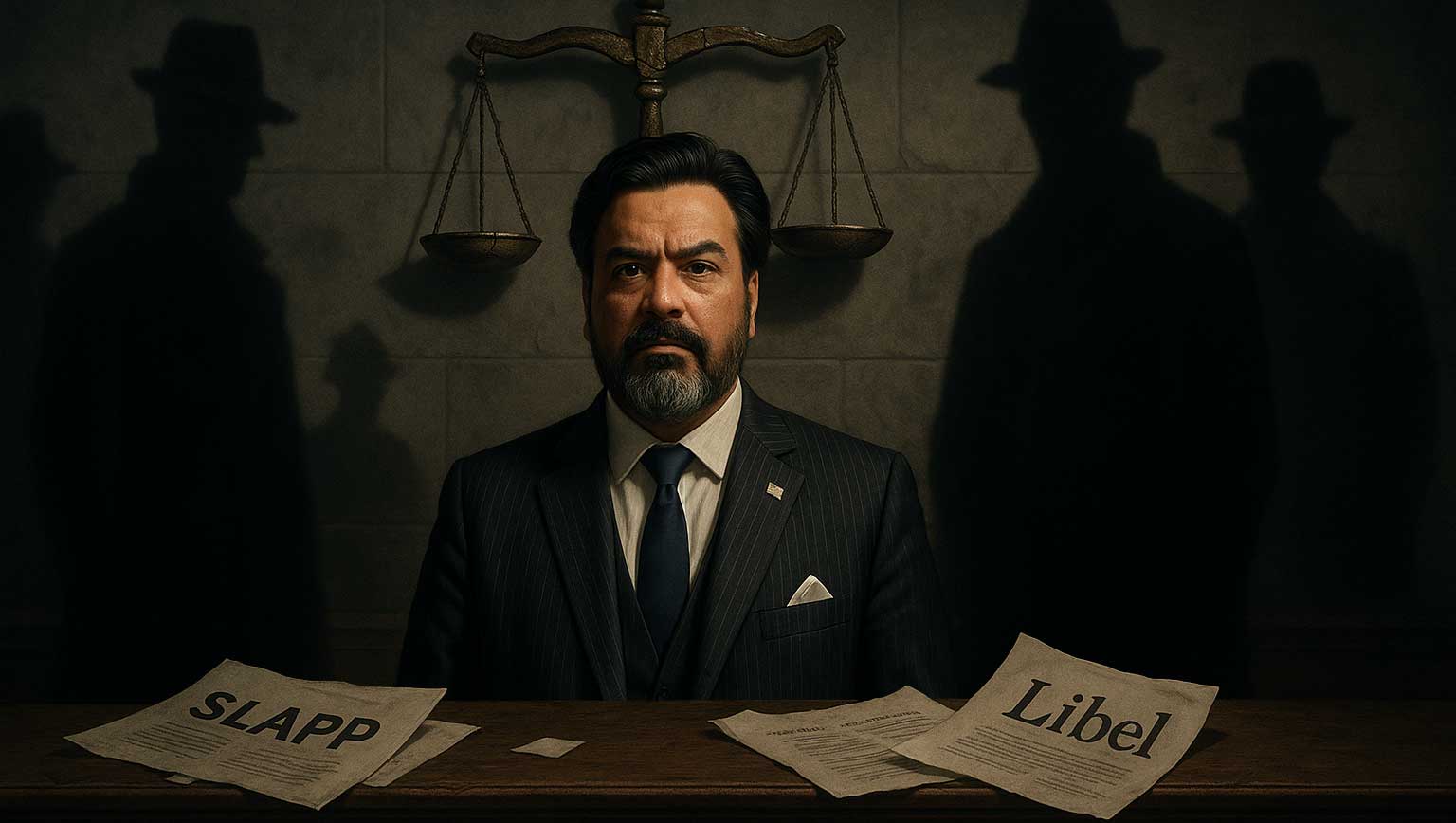

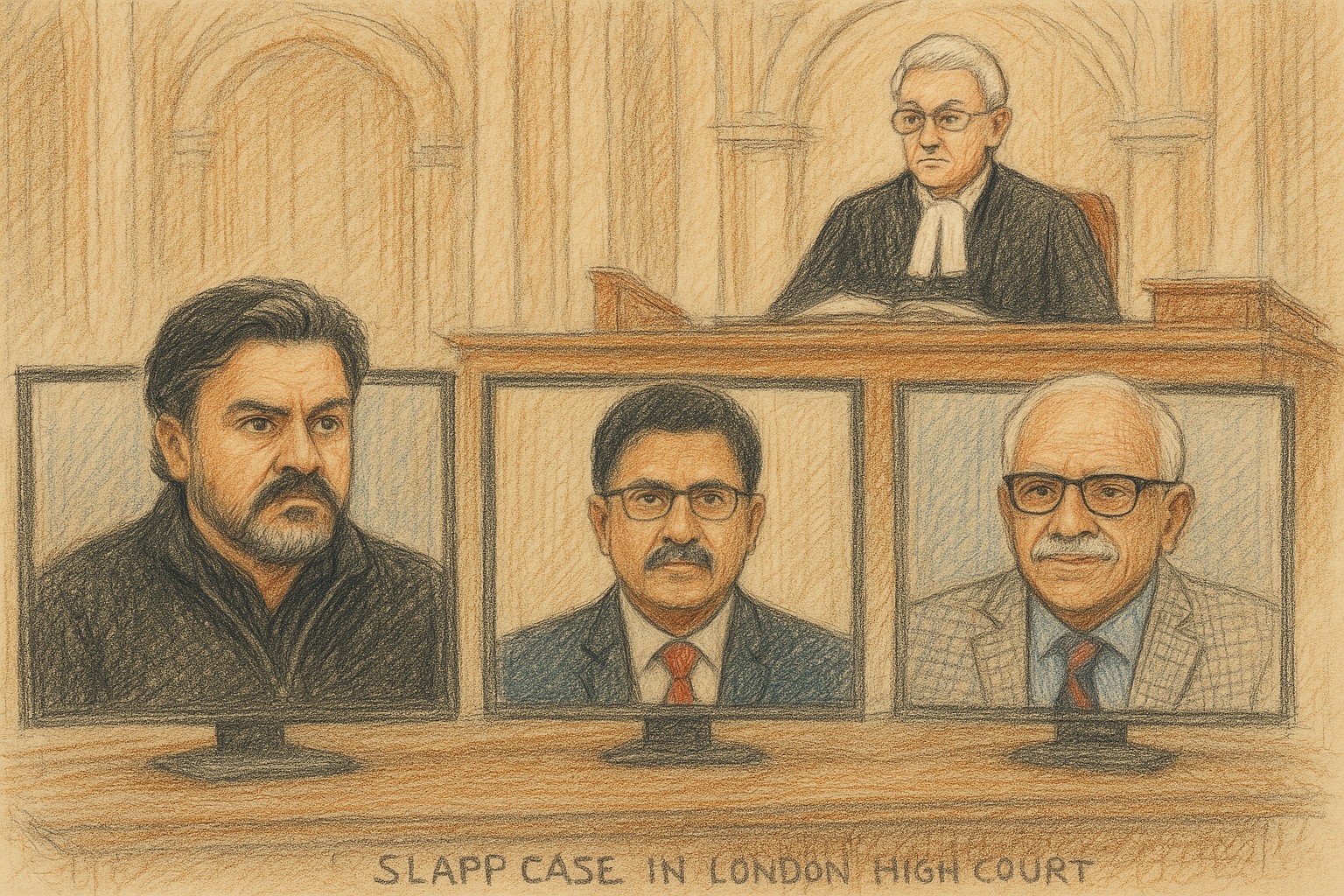

Rashid Naseer claimed his reputation had been damaged in the UK, despite never residing there. The judge questioned the plausibility of a reputation existing in the UK for someone based in Pakistan. The core legal question became whether there was serious reputational harm suffered within UK jurisdiction due to Adil Raja’s publications.

This aspect of jurisdiction became pivotal. British defamation law requires that the alleged harm be serious and demonstrable within the UK. But Rashid’s argument, built on digital viewership metrics and a handful of anecdotal references, appeared speculative. When asked to show evidence of specific reputational damage or threats he faced in the UK, Rashid faltered. He was unable to produce concrete documentation, nor could he identify verifiable witnesses from within the UK who viewed Adil’s statements as damaging.

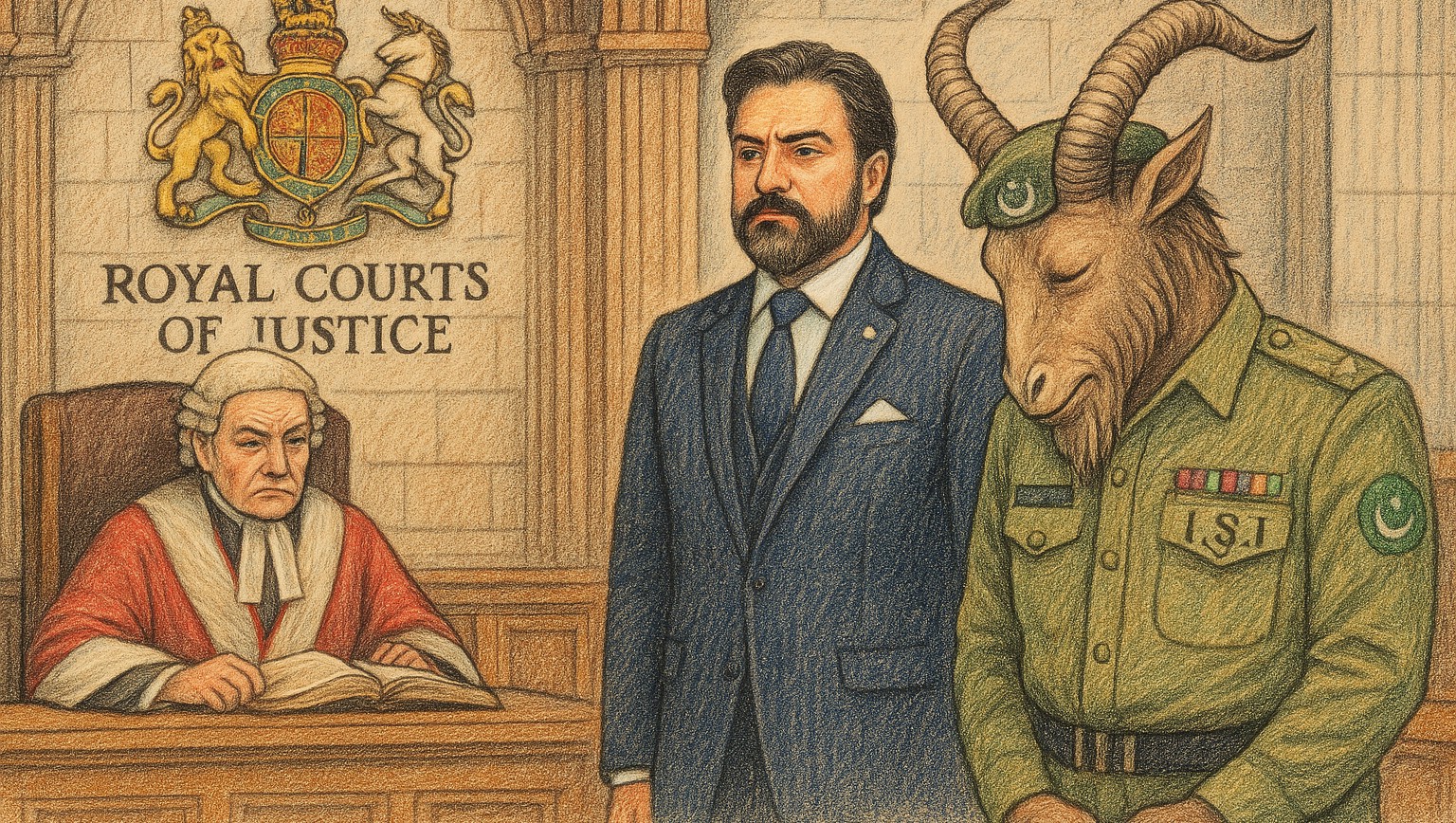

Adil Raja forcefully asserted his defence under journalistic privilege and public interest. He insisted his reporting was drawn from credible ISI sources and asserted his multi-layered system of sourcing and buffering to protect identities. He acknowledged the absence of written notes but underscored the integrity and consistency of his information, noting that much of what he had published ultimately turned out to be accurate.

The judge probed the absence of documentation, noting the burden of proof lay with Adil to justify the responsible publication of defamatory claims. Yet Adil’s passionate delivery, consistent narrative, and emphasis on systemic abuse by the ISI helped balance the lack of formal legal polish.

Adil’s defence, though lacking in documentary formality, leaned heavily on precedent and principle. He argued that journalism in exile, particularly when confronting powerful authoritarian structures, cannot function like Western newsrooms with complete paper trails. Protecting sources is paramount, and in regimes like Pakistan’s, documentation is often a death sentence.

During cross-examination, Rashid Naseer struggled to provide credible evidence of serious harm. He failed to substantiate threats or reputational damage and gave inconsistent responses. His credibility was eroded, and the judge appeared unconvinced by vague assertions unsupported by documentation.

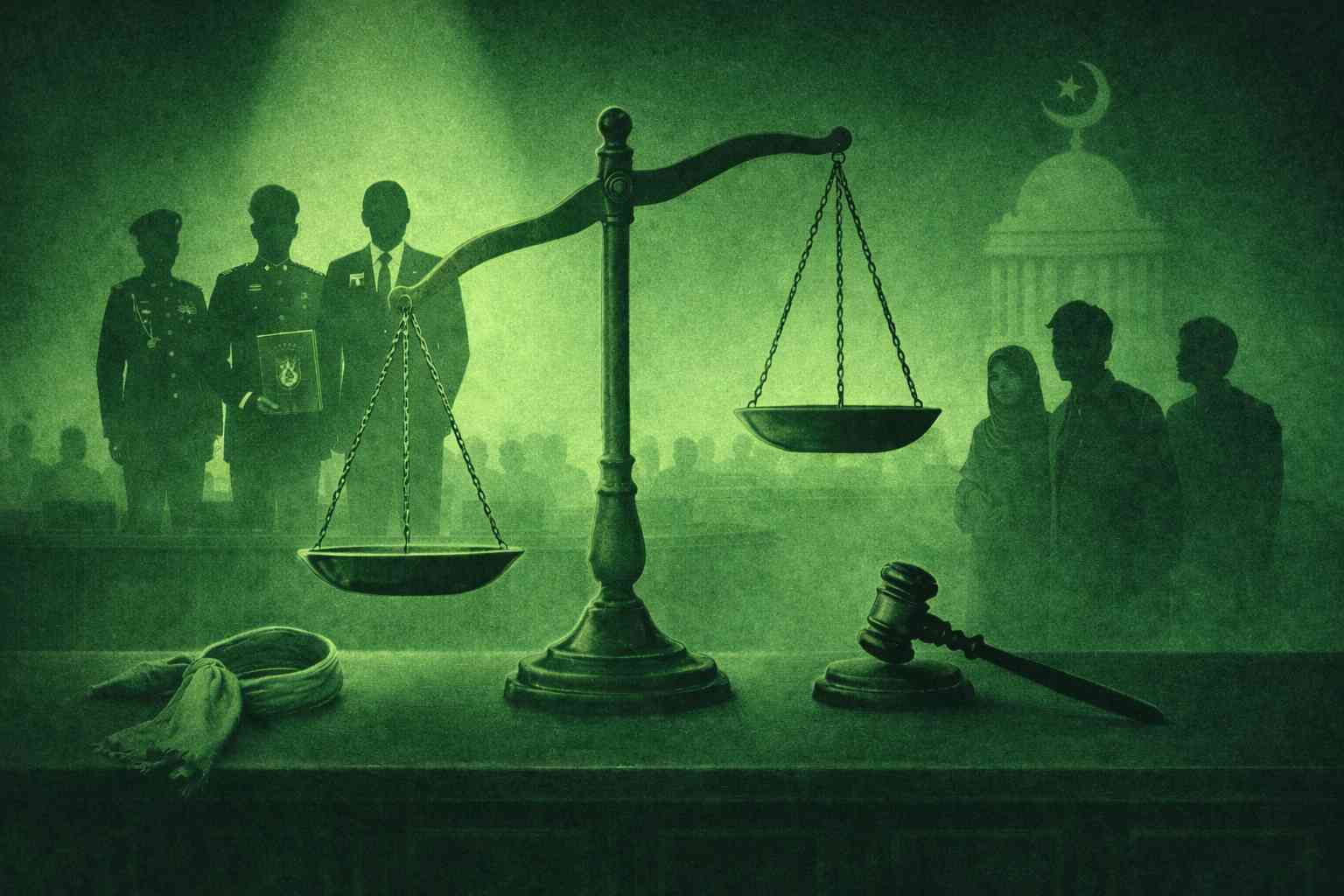

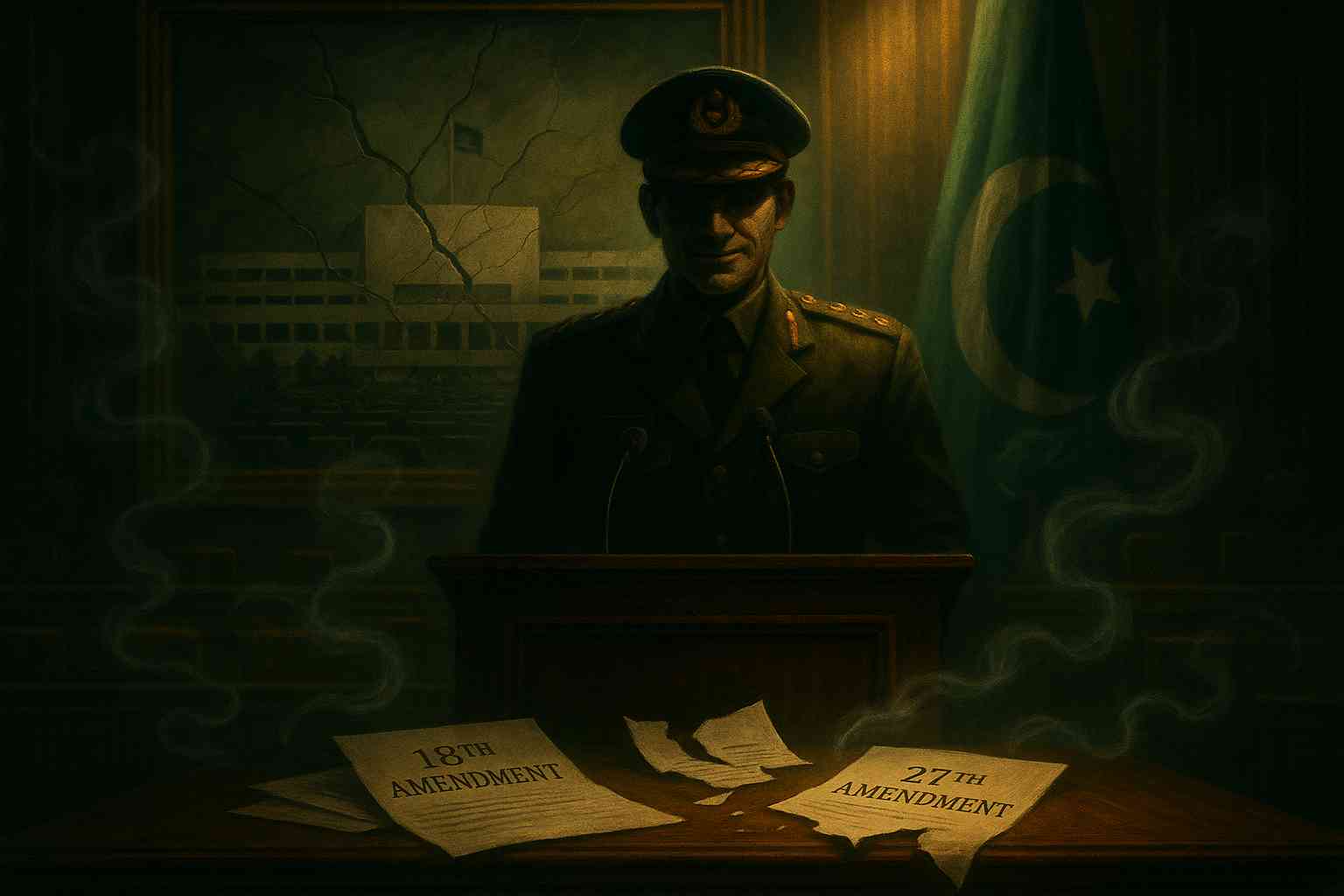

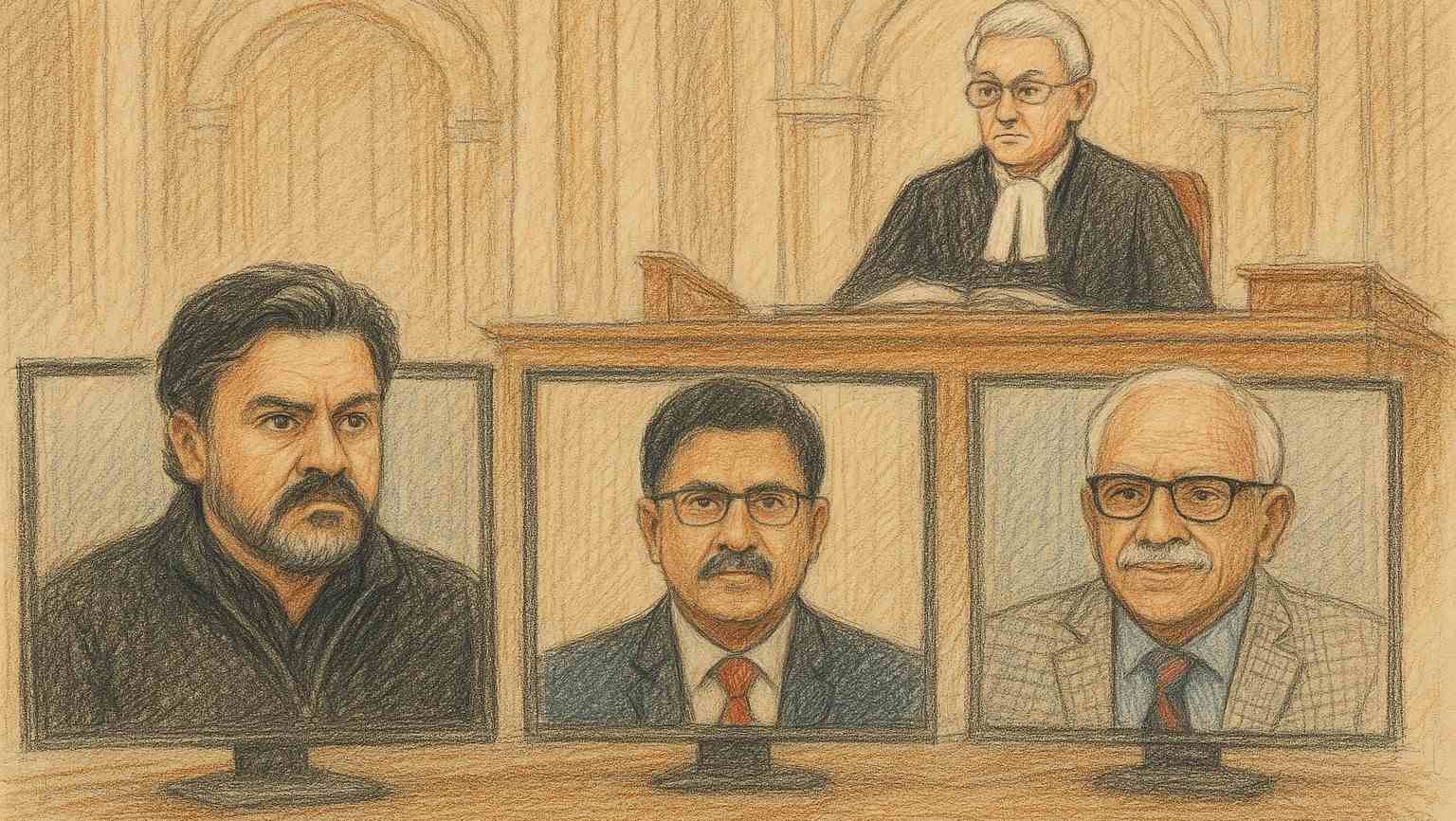

Defence witnesses were damning in their portrayal of ISI interference. Shaheen Sehbai, Shahzad Akbar, and Akbar Hussain offered testimony describing a pattern of state-backed manipulation across judiciary, media, and elections. They portrayed Rashid as not merely complicit but a key actor within the ISI’s internal architecture of control.

Sehbai added levity, joking that while political opponents were once charged with buffalo theft, he himself had faced a bizarre charge of washing machine theft during the Musharraf regime. It prompted rare laughter, even from the judge.

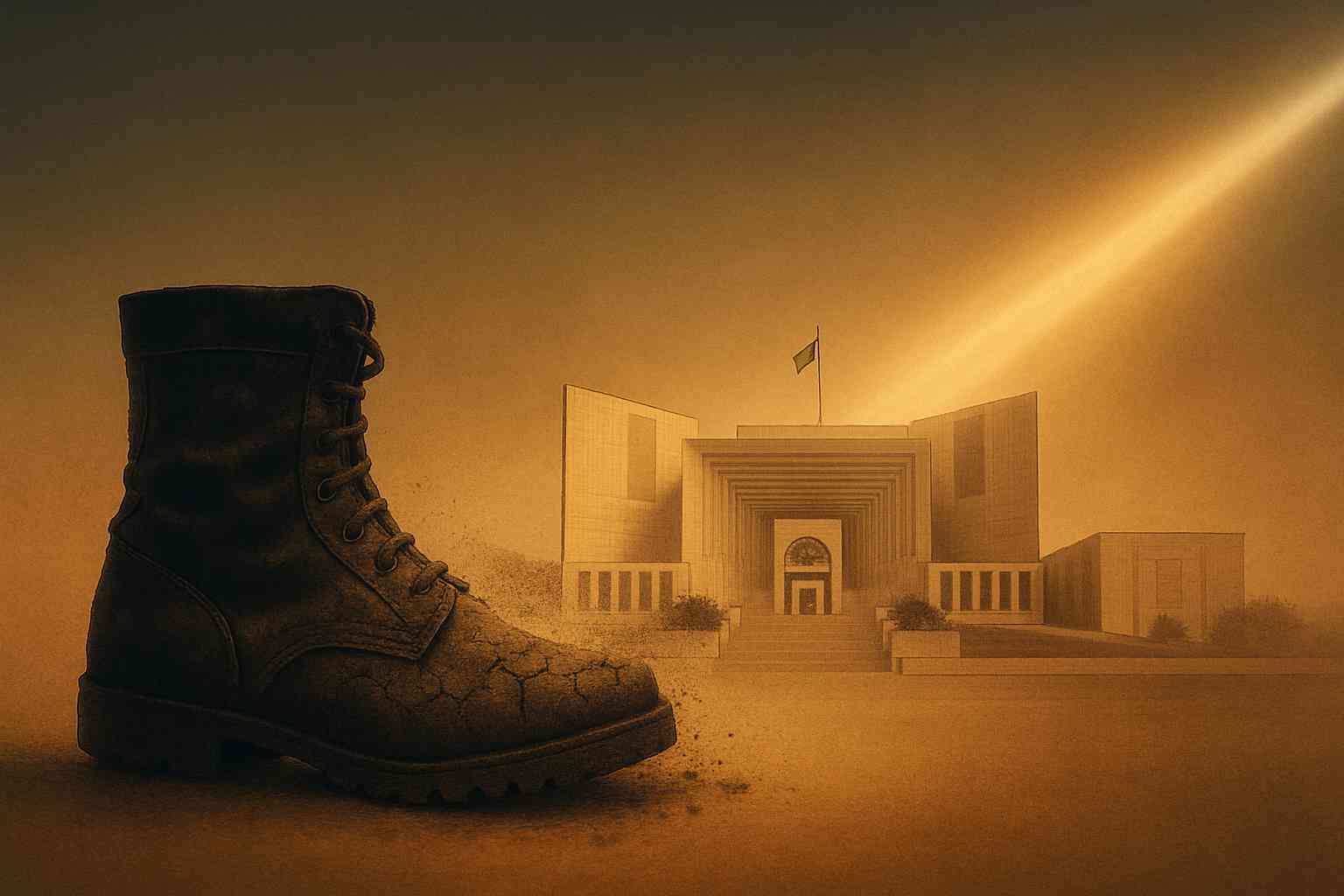

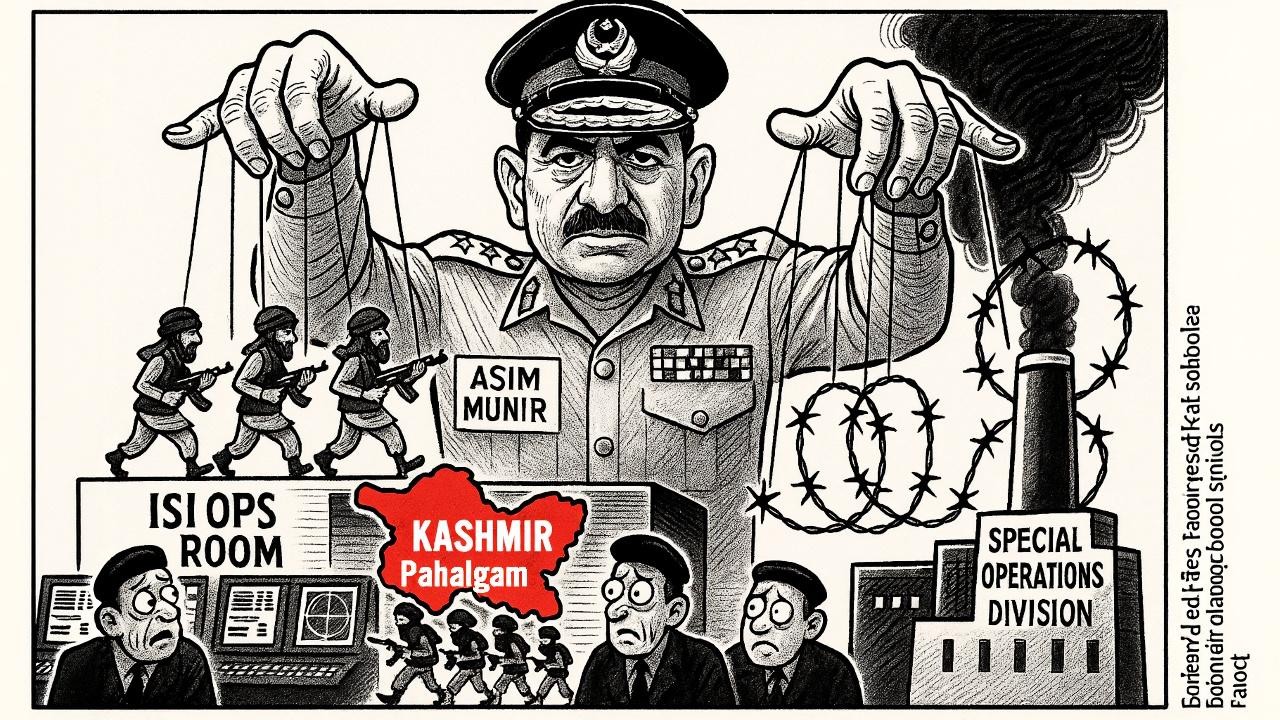

Shaheen Sehbai painted ISI as an “invisible elephant” in the room, omnipresent yet unaccountable. Colnol Akbar said that the elephant is quite visible with its feet trampling the people of Pakistan. Shahzad Akbar described acid attacks, travel bans, and other reprisals he endured, casting light on the institutional retaliation against whistleblowers.

It also appeared that Rashid’s legal fees were being financed by ISI-linked sources, raising further doubts about the independence and authenticity of his claim. One defence witness stated bluntly that the ISI’s real aim was to set a precedent—use UK courts to silence dissenters in exile. If successful, this case would open the floodgates to similar cases against journalists critical of Pakistan’s security establishment.

As arguments closed, the judge reserved judgment, stressing the need for deep consideration of the complex intersection between journalism, national security, and speech. He noted that a fully reasoned judgment would follow, either the following week or after the summer break.

At its core, the case is about whether Adil Raja operated within the bounds of responsible journalism or crossed into the territory of reckless defamation. Equally, it challenges whether Rashid Naseer possessed any standing in the UK to begin with, and whether any meaningful harm was truly suffered.

In all likelihood, the weight of evidence leans in Adil’s favour. Rashid’s claim, shaped and supported by ISI, appears flimsy and manufactured. The expectation is that the judge may dismiss the case while advising Adil to strengthen documentation practices going forward.

But the larger implications cannot be ignored. British courts are now being asked to adjudicate defamation cases filed by foreign intelligence operatives who claim harm to reputations they’ve never publicly held in the UK. If this case is not dismissed with strong language, it may embolden authoritarian regimes to exploit British law to muzzle critics globally.

This case, however, is bigger than either man. It is a referendum on British judicial integrity in the face of transnational state influence. A test of whether the courts will bend to power or stand with press freedom, transparency, and truth in a shifting geopolitical theatre.

The verdict will either affirm that UK law is not a tool for foreign authoritarian censorship or mark the beginning of a troubling new precedent. The courtroom may be in London, but the implications stretch across borders—from Islamabad to Dubai, from exile to influence. The fight for truth, credibility, and the soul of journalism in hostile terrain has rarely found a more symbolic battleground than this one.