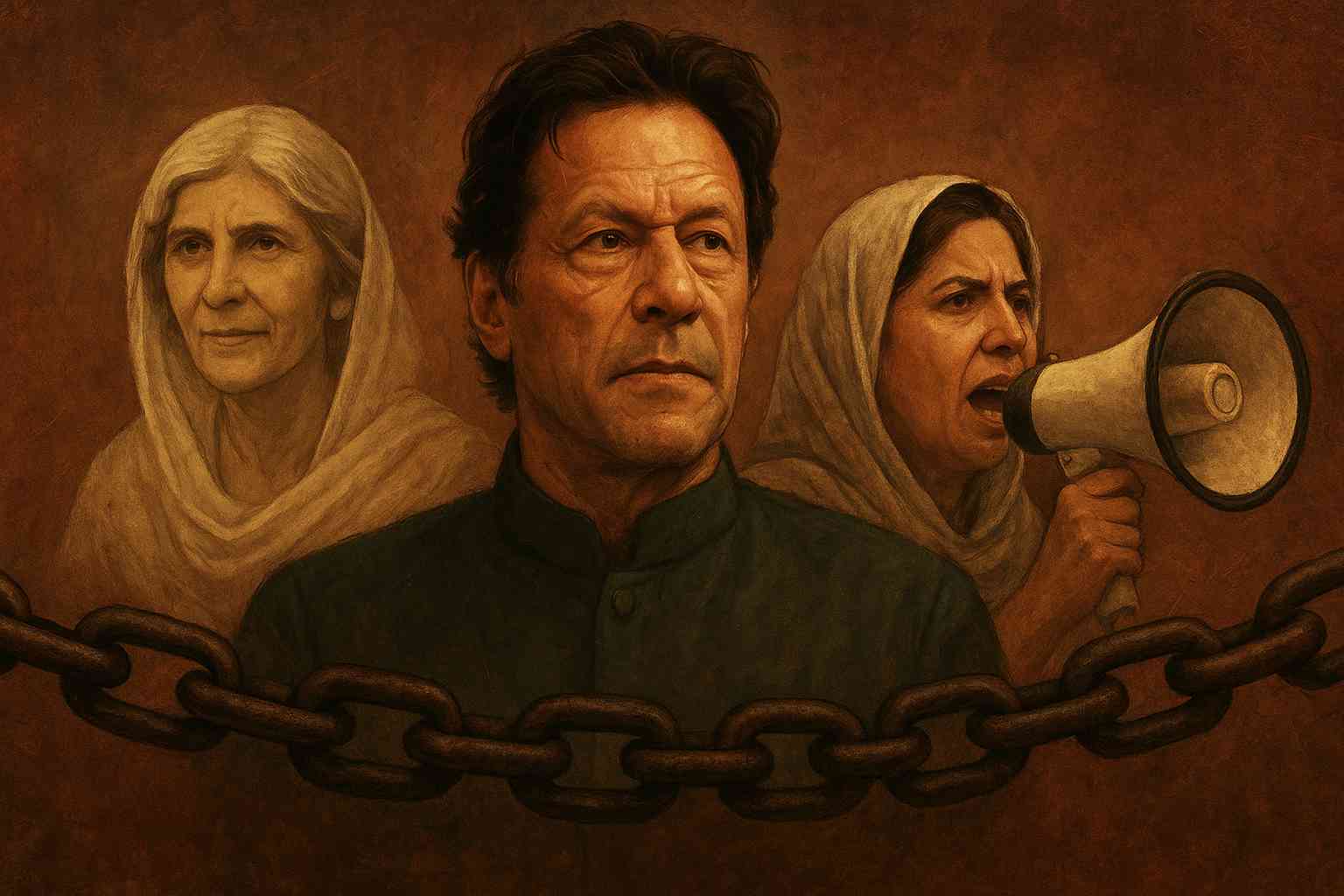

“The dazzling veneer of feminism may momentarily blind the eye, yet it is stretched thin over a void concealing its own rot and contradictions. Into that very void, however, erupts the fierce flame of women whom this ideology secretly fears. Women who embody strength in its indigenous form, unbothered with Western approval. One such flame, searing through that darkness, is Mai Jindo of Tindo Bahawal, Sindh.”

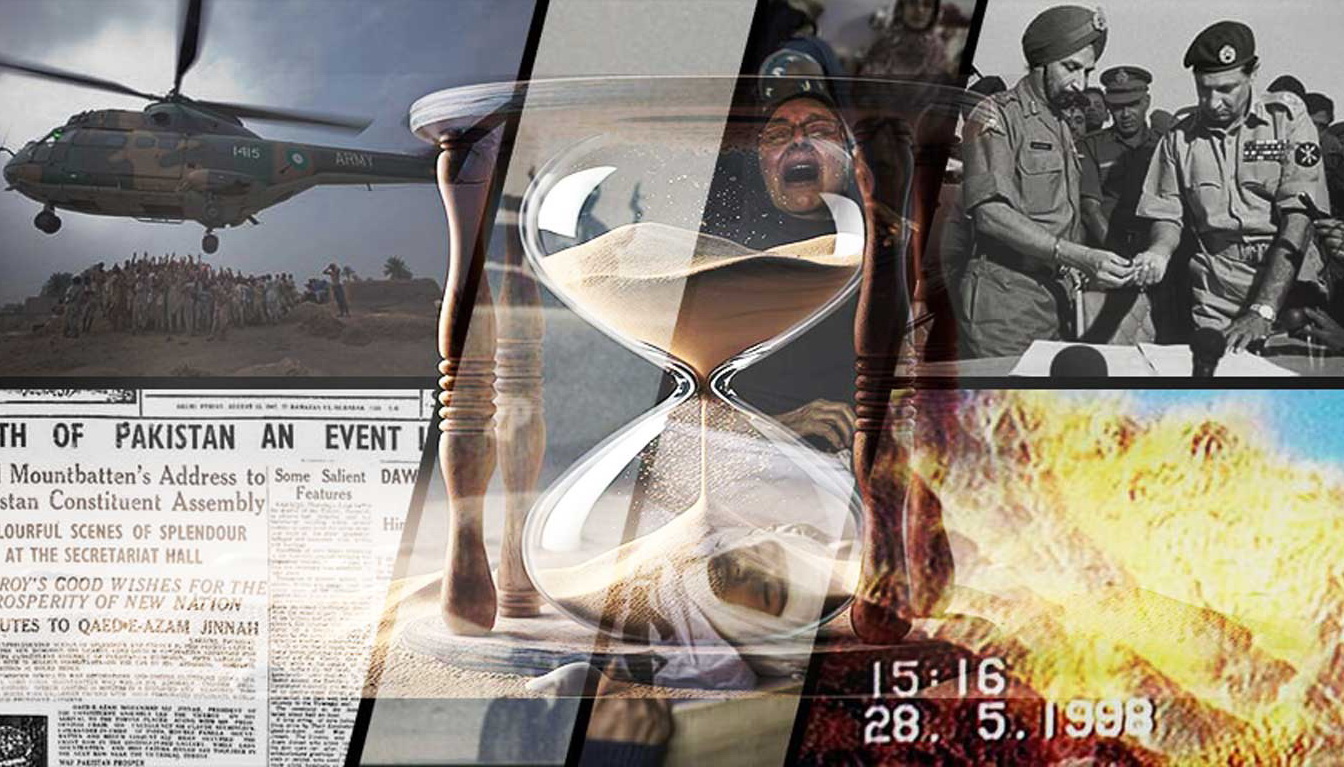

Feminism transitioned into its “Third Phase” in 1992, following Anita Hill’s historic testimony in a sexual harassment case against Supreme Court nominee “Clarence Thomas”. The world basked in the glory of women empowerment. That same year, dubbed the “Year of the Woman,” saw an unprecedented number of women elected to U.S Congress.

Amidst this global celebration that masked exploitation as “women empowerment”, stood a woman in Tindo Bahawal, Sindh. Her eyes casting a stone-cold gaze upon the bodies of her 3 sons.

On 5 June 1992, a contingent of Pakistan Army, led by Major Arshad Jameel, raided the village of Tando Bahawal, on the outskirts of Hyderabad, Sindh, kidnapped nine villagers and later shot them dead on the bank of the Indus River near Jamshoro. The dead included Mai Jindo’s two sons, Bahadur and Manthar, and a son-in-law, Haji Akram.

Maj Arshad Jamil had been deputed in Sindh as a part of Operation Clean-up (also known as Operation Blue Fox), launched by the Sindh Police and Pakistan Rangers, with additional support from Pakistan Army and intelligence agencies, under directives issued by Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif. The major and his jawans alleged that the villagers were terrorists who had links to the Indian Army and its intelligence agency—the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW). They also claimed that they had recovered a large quantity of sophisticated weapons from them.

In a display that defied typical primary human response, Mai Jindo refused to shed a single tear and instead decided to remove her gauntlets against the state and its wretched tyrants. She vigorously rejected these bogus allegations and tried to convince a host of journalists to raise voice for her sons, son-in-law and others who had been killed in this tragic incident. She insisted that the dead were neither dacoits nor terrorists. They were affiliated neither with the Indian Army nor the RAW. Instead, they were simple village farmers.

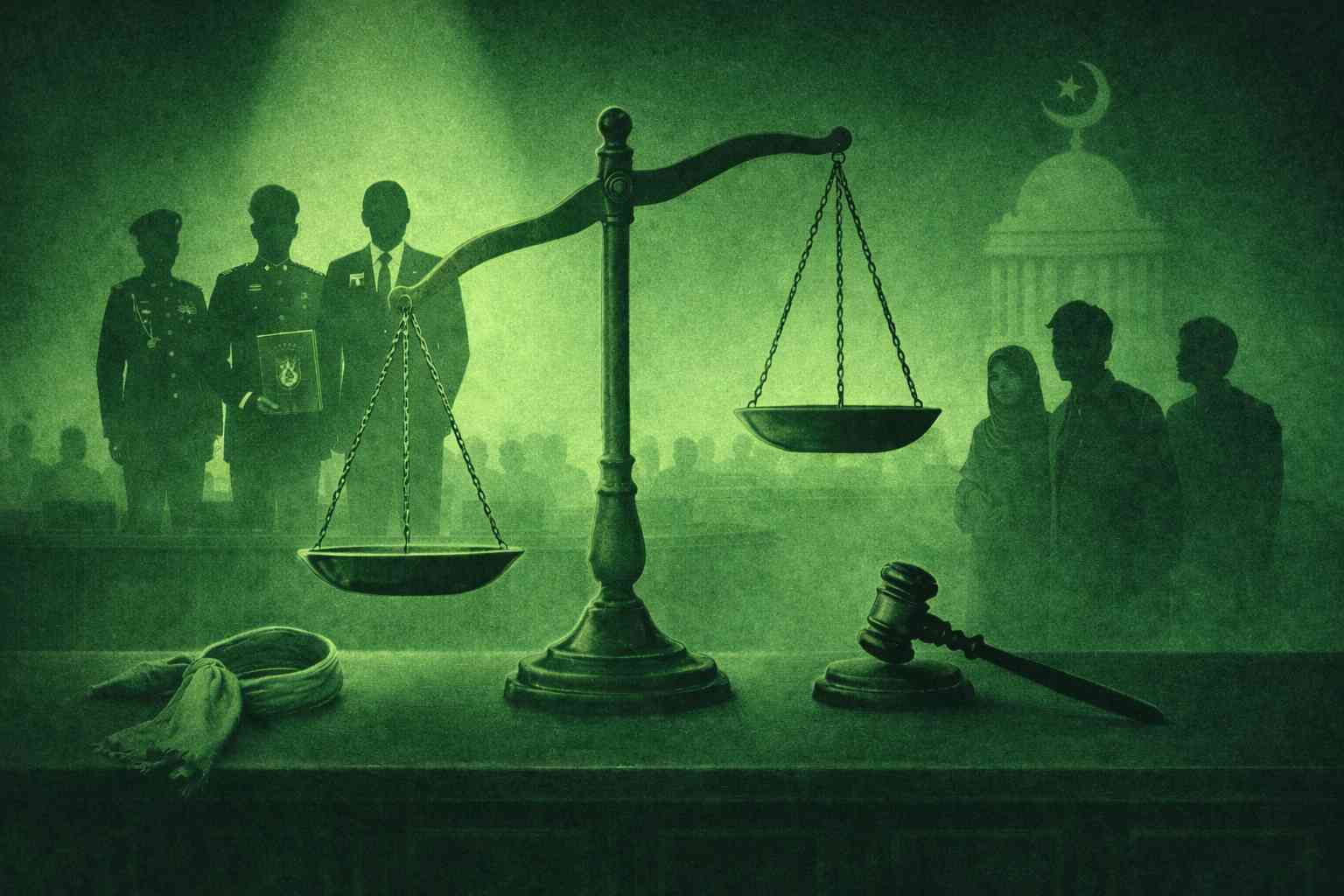

The parable that one must have Prophet Noah’s (peace be upon him) age, Ayub’s (peace be upon him) patience, and Qaroon’s wealth to get justice perfectly portrays how Pakistan’s judicial system performs. However, in Mai Jindo’s case the cost was turned up a notch. As years passed and verdicts stagnated in bureaucratic limbo, two of her daughters — Hakimzadi and Zaibunissa — immolated themselves outside anti-terrorism court on September 11, 1996, as the final act of protest.

Whether it was out of conscience or compulsion, this tragedy jolted Pakistan’s Judicial System from its royal slumber which On October 28, 1996, finally sentenced Maj Arshad Jamil to execution by hanging in Hyderabad Central Jail while the jawans were sentenced to life imprisonment.

The dam holding pain and tears finally broke, and Mai Jindo allowed herself to cry to her heart’s content. Talking at a programme for the International Women’s Day at the Karachi Press Club on March 8, 2012, Mai Jindo said,

“A woman can do anything she wants, if only she is committed to it.”

The dazzling veneer of feminism may momentarily blind the eye, yet it is stretched thin over a void concealing its own rot and contradictions. Into that very void, however, erupts the fierce flame of women whom this ideology secretly fears. Women who embody strength in its indigenous form, unbothered with Western approval. One such flame, searing through that darkness, is Mai Jindo of Tindo Bahawal, Sindh.

Young mothers should burn this tale into their minds as a testament to women’s empowerment, while men must remember that if we do not consciously resist the tyranny of the elite, its relentless march will ultimately consume the lives and honor of the women we hold dear.

In Sha Allah Khair.

Ali Khan is an independent contractor in the trucking industry with a background in Electrical Engineering. Passionate about politics and current affairs, he closely follows global and regional developments to offer grounded, people-centric perspectives on contemporary issues.